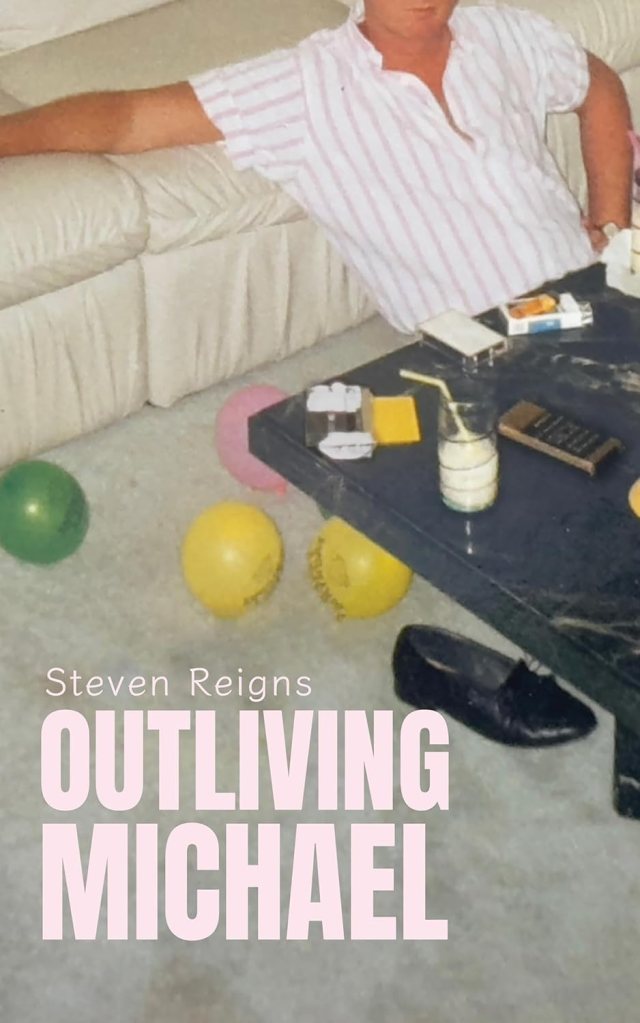

Steven Reigns’s Outliving Michael is a book that is personal and communal. In elegizing his friend Michael Church, Reigns constructs a book of poetry that is both testimony and art. In this collection, Reigns carries the weight of his private grief while speaking to the broader issues of the AIDS crisis. It is a tender archive of memory that survived, alive and well. Reigns’s language rarely strays into excess. It is precise. The stark lyricism heightens its force. Consider the economy of: “After Michael died,/most of my recollections/began with/After Michael died.”

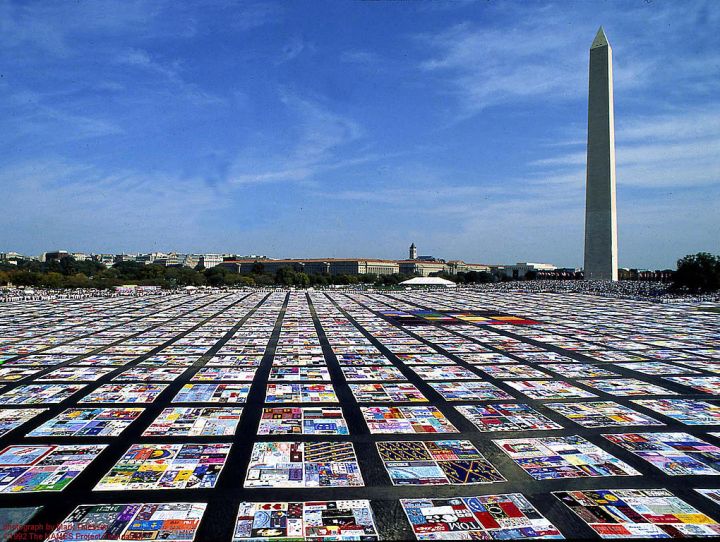

The phrasing enacts the structure of grief, where every recollection is bent around the absence. This is not ornament for its own sake, but a reflection of mourning. It is Reigns’s ability to let form carry emotional weight. Readers familiar with Reigns’s Inheritance and A Quilt for David will recognize this impulse toward merging personal narrative with collective history. In Outliving Michael, the register feels more raw and more vulnerable.

Michael enters the collection vividly, first glimpsed in the blinking haze of Studio 54, where he worked “strawberry-haired, sweating, in/a white T-shirt, bar rag in his/low-slung jeans, bottle of poppers/in his pocket as he danced./AIDS was already in/the room but not in his body,/and no one knew anything anyway.” The passage captures Michael’s physical presence in a very specific moment in time, refracted through historical hindsight causing his exuberant youth to be already shadowed by catastrophe.

Beauty and joy refracted through historical hindsight resonate through the collection. Thankfully, the poems resist the flattening solemnity of elegy. They are often humorous without losing their sweetness. In one, Michael organizes stacks of funeral cards into the courses of a meal: “Jose–entrée/Michael–hors d’oeuvre…Ramón–dessert.” Wit not just as a coping mechanism, but also as a survival tool.

What elevates Outliving Michael is its intimacy and its insistence on documentation. Reigns frames remembrance as an act of resistance, writing: “Here is a man who meant something to me/and who could mean something to you./Here is a man who lived a large life cut short.” Here the simple naming of facts and details is a resistance to forgetting as it pushes back against silence. These lines underscore the collection’s archival dimension. The moments he memorializes and capture are almost a catalogue of not only one man’s life, but of a moment in our American history, one that the poems subtly contextualize.

The poems do not merely preserve memory; they document and reorganize it, transforming personal loss into a shared archive through which those experiencing grief or who lived through the AIDS crisis can learn and relate. In one poem Reigns says:

...He already knew. That

the virus was a killer,

that he should

be cautious, and that the

medical professionals

we wanted to trust

we shouldn't.

The closing poem’s stark tally—“Michael’s days totaled 15,532”—operates as both record and reckoning, stating the irrefutable specificity of a single life.

With Outliving Michael, Reigns has given us more than a tribute. The tonal range, the precision of imagery, and the collection’s unflinching clarity affirm poetry’s enduring role as witness. Beautiful, accessible and uncompromising, the book belongs both to the personal realm of friendship and to the collective archive of history.