I am not the first to hitch my wagon to Baudelaire’s Paris Spleen (1869), as the most punk rock text punk rockers ever gave the literary world. It’s not just the sensual fervor of “Get Drunk” (“you should be drunk without respite”) or the cosmic interlocution of “The Stranger” (“Tell me, enigmatical man, whom do you love best,”), Baudelaire provides a blueprint that punks from Iggy Pop to Patty Smith have championed, emulated, and echoed.

Baudelaire also pioneered the use of prose poems in poetry; that is, he wrote prose with a poetic flair, and forced other writers to contend with formal, historical constraints inherent in French Poetry. Baudelaire was just one writer, but there were many Symbolists. However, in 1886, when poet and critic Jean Moréas published “Le Symbolisme” (“Symbolism, or Symbolist Manifesto,” etc), Moréas was sure to roll call the triumvirate of Charles Baudelaire, Stéphane Mallarmé, and Paul Verlaine to distinguish them from the staid Romanticism of the poets en vogue, the Decadents. Baudelaire changed the way poems could look in print, but he also amplified what subjects the poets of the era would entertain–what discourses they would negotiate with their minds.

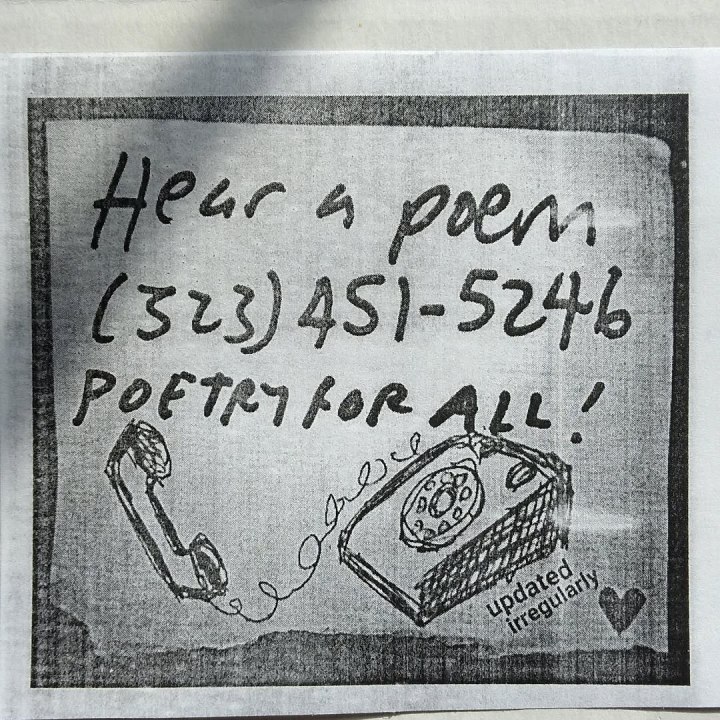

Gussin’s poems aren’t punk rock per se, but they break convention and stir the shit in ways that force the reader to rethink their stances. Gussin’s poems invite us to identify our prejudices about who consumes poetry, and who gets the privilege of championing the idea of poetry as a public utility, as something meant for public consumption and supposedly enjoyed like bread, when most people have to work to eat.

There is scant musicality in Gussin’s poems, but there are quixotic philosophical quandaries (“I Think I’d Be Pretty Good at an Orgy”) and staunch political statements (“The Meeting”). Moreover, all types of characters abound in Gussin’s poetry, not just punks, but a roster of characters, from ladies named “Ingrid” at a “vegan restaurant in Santa Monica” to a “duffel bag man with three teeth,” that make it clear that with the variance in socio-economic order, Gussin is really writing about how all of humanity can sometimes be pretty shit and/or execrable.

Most of Gussin’s poems rely on a blue-collar aesthetic and an authenticity that are hard funks to fake; they pack a punch from the periphery of this poetry thing, but they do so in plain English, and without making the reader feel dumb.

For example, “Lil Rock” from his collection The $22 Cheesecake and More is a poetic dialogue between two strangers at a bus stop that commences with an out-of-pocket question, “Are you Italian?” It’s an out-of-pocket question because, where are you from? is usually followed by what are you?—two innocuous-sounding questions that typically lead to racially insensitive statements and claims.

The speaker in the poem informs the interlocutor that they are “Jewish,” and that they know the neighborhood because their “grandmother grew up there.” When the speaker is challenged by the stranger at the bus stop to admit they like Jewish people more than regular people, the speaker counters with, “People from Little Rock, Arkansas always make me feel good.”

The stranger at the bus stop doesn’t know how to deal with the speaker’s confession that “I love all people,” and the poem’s real strength comes from the tension that rises between two strangers as they vie for a semblance of familiarity. The speaker is not only able to convince the stranger of his predilection for people from Little Rock, but also leaves the stranger with several morsels of food for thought, “there’s a whole real ass fucking world out there, it’s not on TV, and it’s not in any glossy magazine, but it’s 100% there.”

Don’t fret, though, because there is plenty of classic poetry fare in Gussin’s kinky, cat-loving collection, like paramours and lovers, but Gussin doesn’t grunt to make those elements poetic—he renders them through a punk-rock prism of liminality that the narratives and anecdotes adopt a poetic sheen. In this way, what Gussin accomplishes seems nominal and imperceptible, but if you’re paying attention, his poems leave the hemispheres of your brain like a freshly laid bear trap. For example, in “I Understand the Risk I Take By Sharing This View” the speaker begins with a tawdry, peculiar confession–”…I believe there’s nothing/more erotic in the York Valley than her storm drains in a heavy rain,”—that also personifies Highland Park–that is—transforms the nabe into a rain-drenched and “back arched” rain goddess serviced by two splendid “floodplains.” The point is to laud the civic-minded storm drains because they do the “sexy” work of keeping society whole and in working shape, “the storm drains deserves to be fawned over and treated with/obsessive appreciation.”

Some of the poems in Daryl Gussin’s The $22 Cheesecake… remind me of the quasi-philosophical, discursive, 18-wheeler lines C.K. Williams made “coo” in Repair (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2000). Poems like “A Confession & a Communion,” “Maintenance Light,” and “For Johnnie and Nehamias, This is the Wedding Present I Never Got You” force the reader’s eye to track from right to left as if the sentence were an infinite tennis match. These plainly Janed, trailer-long sentences allow the speaker to wend their way through difficult sentiments and arrive at unique connotations.

Because The $22 Cheesecake and More is a distillation of three separate zines: The Hermit Thrush, The Western Stubby, and The Forgotten Edge, it is hard to say whether any of the sections supersedes the others. But what one can say is that the curation of the poems, the way Gussin sets them up like bowling pins to be knocked down, gives novice readers an accurate assessment of Gussin’s poetic prowess. We are in the hands of a narrator who addresses the spiritual world in a way that is materially expansive, but we are also at the mercy of a materialist who can spin webs of spiritual virtuosity.

The $22 Cheesecake…’s aesthetic is that of a zine—a mimeographed home-made book—and the book’s post-apocalyptic purple/lavender cover is a gloriously matted photograph of the author crashing on a couch as a tabby cat nestles between their legs. The book’s real strength is the way that it plays with Dualism, with both the material and the spirit of poetry. The poems in $22 Cheesecake… originally appeared in three separate zines: The Hermit Thrush, The Western Stubby, and The Forgotten Edge. Gussin does an exceptional job of shuffling the poems to constitute a best-of book. But make no mistake, for Gussin, zines are a higher form of collation than a measly book, and that fluidity is evident in these poems as well.

Some of Gussin’s poems remind me of speedball anecdotes told by a haggard bard or a New York Doll. Others remind me of a philosophy professor with their pockets turned inside out, or a modern-day sophist, or maybe even an anarchist actuary. In other words, Gussin’s lines are poetically impious and propulsively philosophical, but are also able to scaffold working-class scenarios of supremely important nobodies into generalist tautologies of reflexive elan.

Most importantly, the poems in Gussin’s The $22 Cheesecake… read like reckonings with the speaker’s own shortcomings, and their refusal to continue to “run” that game of oblivion so many of us do. For example, in “Run,” the speaker starts by declaiming, “I used to be able to run from what which was crushing my soul,” before launching into, “Now, at forty, the high blood pressure, unhealed wounds, and/hemorrhoids all come with me, you can’t outrun that which can/outrace time,” and so this turn leads the reader into thinking that Gussin has this clarity because of how his age makes him feel. But, by the end of the poem, the readers infers that Gussin isn’t giving us the over-40 talk—the slower you move/the better”—he’s intimating to us that he’s just gaining momentum and wisdom, “You could be what I’m running from, or what I’m running to, I have/enough to run from, I want to run to you.”

Making things look effortless takes a shit-ton of time and requires the patience of a fucking Zen gardener. Without bullshit flourishes and with zero gimmicks, Gussin shows us the humility of his duende–the acuteness of his poetic epistemologies.