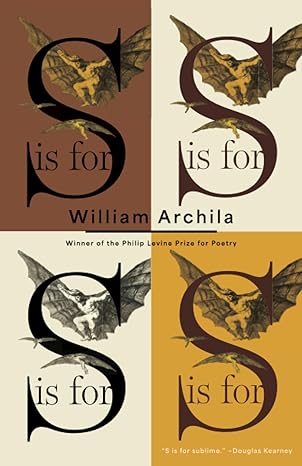

On Sunday at Avenue 50 Studio in Highland Park, three local Salvadoran poets read, discussed their work and shared insights into their identities. “Places We Call Home: Exile, Change and Collective Futures” featured William Archila, Cynthia Guardado and Janel Pineda, Archila and Guardado being published in the recently released anthology Latino Poetry by the Library of America. Edited by Rigoberto Gonzalez, the anthology “includes more than 180 poets, spanning from the 17th century to today, and presents those poems written in Spanish in the original and in English translation” according to its Amazon page.

This April midafternoon was warm and bright, the first event I attended at Avenue 50’s new location. Already present was much of Beyond Baroque’s staff, as they were the bookseller and co-sponsor of the reading and conversation.

The reading was a chance to expand on the conversations the anthology enters into, the narratives and traditions of Latinx poetry. With Greater Los Ángeles being home to the largest diasporic community of Salvadorans in the world, with Salvadoran Americans writing and publishing in greater numbers than ever before, from the likes of Javier Zamora, Christopher Soto and Raquel Gutiérrez, it felt apt to have a reading featuring their stories.

Plus, Guardado read a new poem drawing a connection between the country’s neocolonial practices—from supporting the genocide of Palestinians in Gaza to the current Trump-era deportations of its Latinx residents, especially to El Salvador—carried out without any semblance of due process. By highlighting these interconnected forms of violence and making them personal, the poem helped to set the stage for a discussion on the ongoing impact of U.S. neocolonial policies on the Salvadoran American experience.

Archila, Guardado and Pineda represented three successive generations of Salvadorans and Salvadoran American experience. Archila was born and raised in El Salvador until the civil war forced his family to move to the United States in 1980 when he was 12. Guardado was born in Boyle Heights in the mid 80s, during the height of the civil war, and has traveled often to El Salvador beginning when she was two, during the war. Pineda was born in 1996, after the civil war, and was an adult before she learned El Salvador had gone through a civil war.

It was Pineda who was the moderator, asking the two older poets questions and commenting when she could to expand the conversation. These were questions about their relationship and connection to El Salvador, how Archila came to be a poet and the role that poetry plays in creating change, to speak truth to power in aiding the activism that’s needed to stop Trump’s fascist policies.

Since the presidential election in November, an increasing amount of poetry written by people of color—and more readings and discussions conducted by writers of color that feature themselves and their work—are addressing the issues of neocolonial fascism that continue to terrorize their communities across the country.

A local poet and elementary school teacher at Thursday’s monthly Trenches Full of Poets open mic at Page Against the Machine in Long Beach, spoke about how some of his students confided in him that they had dreams where ICE broke into their school and kidnapped them.

And Pulitzer Prize winner and USC professor, Viet Than Nguyen, has become a vocal advocate in calling for a literature of dissent, calling for the political activism of writers, especially for writers of color, both on and off the page, in confronting these turbulent times of genocide, violations of our first amendment rights, and the weaponization of American border security against students, at a time when our right to dissent has never been more precarious.

It was no surprise that nearly every audience member on Sunday was of Latinx descent.

At one point during the discussion, Archila stated that poetry cannot change the world. Poetry, he said, cannot enact policy.

However, poetry is still vitally important, Archila said, because it shapes how people understand the world by offering new perspectives. Its effects are personal and transformative, for example, to show and build solidarity or to gain a deeper understanding of oneself. That’s why Archila started writing poems, as a way to better understand himself and his identity, while navigating his new life in America. As he became more Americanized and lost his connection to El Salvador, especially as more of his extended family escaped the civil war to settle in the U.S., he found himself stuck between two worlds. He was no longer fully Salvadoran, but not entirely American either.

Both Guardado and Pineda stated a similar experience: With more family living in America, their connection to El Salvador grew weaker and weaker, as there was less of a reason to return. Less of a connection.

But it’s Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele’s friendly relationship with President Trump that connected the discussion to the present turbulent times. Nayib’s agreement to accept non-Salvadoran deportees from the United States—including Latinx American prisoners, both U.S. citizens and legal residents—without regard for whether those deported were actually convicted criminals, into the CECOT prison, helped highlight the connections and negative effects that U.S. colonialism has on other countries and peoples throughout the world. It illustrated how these extra-judicial deportations are part of a Salvadoran legacy of complicity and subjugation under U.S. neocolonialism.

A legacy that produced these three L.A.-based poets who were in conversation Sunday.