But my story differs from others you may have read regarding African American homeowners in Altadena, who were devastated by the Eaton Fire.

Twenty-five years ago, the arms wrapped around mine, which were wrapped around my own shivering frame, belonged to my soon-to-be husband, Phillip. “Where are we?” I asked. I hadn’t seen my breath hang in the air since my last camping trip to the Angeles National Forest.

“This is Altadena,” his voice, our voices, not much above whispers. There were no vehicle horns, no street noises to compete with up there at the tippy top of Lake Avenue where we were visiting my fiancé’s best friend from high school.

All I experienced then was the chill of the 1,900-foot elevation, our quiet, contented breathing and the broad street which sloped downhill in front of us, opening up to myriad urban lights below. The nighttime glitter of the Downtown Los Ángeles skyline and far beyond—wait, was that really the glow of the oil refinery over 30 miles away in the South Bay, where I lived at the time?

Altadena.

That night, I was standing just steps away from what I later learned was the Cobb Estate and Echo Mountain trail. Straddling a historic line of demarcation between what I later learned was east-versus-west-side Altadena.

A year later, when the real estate agent suggested Altadena property number five, my blue-eyed, Irish Catholic husband quizzed him: “What side of Lake is this one on?”

“West,” the agent responded, not looking at me.

Phillip’s lips crimped, but he was silent. The brief exchange meant nothing to me back then and I didn’t bother to inquire.

This house was closer to the foothills than any of the others we had seen. It was a bright, clear day in September and the mountains appeared to change colors, from green patched with dry brown in the foreground, to hazy blues and purples behind.

The agent took us up the driveway, towards a raggedy wood gate with peeling paint—a shade of red, somewhere between brick and chili pepper which would prove a challenge to match during future renovation. The gate nearly toppled open, revealing a large, flat backyard, half paved in brick. I giggled at the pool vac as its bizarre-looking flippers crawled along the bottom of the swimming pool, which dominated the other half of the yard.

Beyond the pool, a terraced hill with stone steps sloped down towards the next street, adding fully landscaped square footage to the property. My allergic nose crinkled from the scents of mature citrus trees: orange, Meyer lemon, tangelo, grapefruit. The leathery, dark green leaves of an avocado tree made a vain attempt to hide its clusters of fruit. It was nearing dusk and tiny white lights began to glow, wrapping the stair railings and the centerpiece oak tree.

The previous owner, son of an immigrant Danish couple surnamed Olesen, was a metal sculptor whose astonishing work was evident all around. What appeared to be shovel heads had been fashioned into masks of horned creatures, welded onto rebar poles, and staked into the soil around trees. A giant pterodactyl with a huge wingspan swung over the pool from a bouncing metal arm fastened to the outside garage wall.

This was Altadena: the artist’s colony at the foot of the San Gabriel Mountains.

Despite there being a ton of “deferred maintenance” and for this city girl born of New York pavements, after wrestling open the master bedroom’s sliding glass doors and soaking in the view of the patio framed by the towering San Gabriels, we were sold.

My first single family home!

The “deferred maintenance” repairs went on and on—including fixing a giant hole in the guest bathroom (which had been hiding from my eyes by the strategic placement of the bathmat)—until we hit our budget of just-enough-to-make-the-house-livable dollars. Two months later, Thanksgiving 1999, Ashton, Phillip and Curry the dog began greeting their new neighbors in Altadena.

“The legacy of redlining resulted in a long-term concentration of Black residents to those parts of Altadena that were closest to the Eaton fire perimeter,” said Lorrie Frasure, quoted in an article by Lois Beckett.

During a walk through my new neighborhood, I met an older Black woman, a welcoming homeowner living a few blocks from me. Our conversation led her to introduce me to the wider neighborhood.

“Back when I was in the market to buy, no one would sell to Black people. Of course, they didn’t say it like that,” she sucked her teeth, reliving her deep frustration and anger. “They came up with every other excuse.”

Finally, she said, a white ally volunteered to act as her “proxy,” purchasing the home under his name and deeding it back to my neighbor.

I knew nothing about the legacy of African American homeownership in Altadena. In fact, it was my Caucasian mother-in-law who educated me about the displacement of many minorities due to the planned extension of the Long Beach Freeway, which would’ve cut straight through the heart of South Pasadena and Pasadena, just to connect to the 110 freeway. It was never even completed.

In 1960, Altadena’s Black population was under four percent; over the next 15 years, half the white population left and was replaced by people of color, many of whom settled on the west side of town after being displaced by Pasadena’s redevelopment and freeway projects.

More recently, years of gentrification and rising housing prices in Altadena have been accompanied by a steady reduction in the city’s proportion of Black residents, who once made up 43% of the city.

By 2020, the United States Census reported that our African American population had shrunk to 18% in Altadena.

However, 81% of Black residents in Altadena still owned their homes—nearly double the national average.

My dear friend from church, Tecora, was a barrier breaker in more than one respect and I can only imagine the trials she faced. She married her white husband in the 1950s and they were early buyers in west-side Altadena. Their home survived both the Station and Kinneola fires.

In the first days of the Station Fire which ignited on Wednesday, August 26, 2009, experts believed it would not cross the ridgeline and move east towards Altadena. But it did.

Residents of my block exchanged predictions, gasps and stories of previous conflagrations as we stood together in community: Black, white, Christian/Catholic, Jewish, Mexicano, Salvadoreño, South American. In all our diverse kumbaya, in the middle of the street, eyes were trained on the smoke and fires in La Cañada Flintridge, the city bordering us on the west.

It was during this neighborhood-wide vigil that I learned the Olesen family was visiting relatives in Denmark when the 1993 Kinneola Fire struck. All they could do was remain glued to TV news in prayer and terror as the fire crept closer to their—and what was to become my—future home. The flames scorching pine trees and chaparral above Altadena.

Then miracle of miracles: the winds changed direction and our town was spared.

“Call me if the fire jumps the ridge again,” my neighbor Sergio requested, jostling me back to the present, as he hurried away to lock up his office. Back then, I didn’t know what “jumping the ridge” meant, but a day later I received my education in the field.

In 2009, we had time. News reports, law enforcement and fire departments kept us informed. I had time to call two hotels down the hill in Pasadena to make arrangements, just in case. Time enough to pack the “go bags” with essential documents, irreplaceable photos, Curry’s travel bowls, dog food and treats. Time to be sure we had phone and laptop chargers. When the Altadena Sheriffs finally cruised our street calling “Mandatory Evacuation!” over their bullhorns, I still had minutes to check on my neighbor, who had very recently rented the house to the left, to be sure she heard the announcement and had a place to go.

Curry and I accepted our mandated chill-time at the Westin Pasadena Hotel for two nights, until the evacuation order was lifted. Phillip snuck back up the hill to Altadena after the first night, following the lead of several of the men in our neighborhood who stayed behind to “defend the homes.”

Our house, like many others, required remediation for smoke and soot. But otherwise, Altadena escaped.

By mid-2011, my marriage was in big trouble. What began as a rocky trail became a twelve-year desert trek, with few oases in between. Early on, I became the full-time breadwinner. Even after a year of pastoral counseling, the grand announcement came: “This isn’t working,” Phillip said. “We have to start the process of moving on.”

I hated him and now I hated the house I had worked so hard for. I cried so continuously one evening, I had to ferry myself to the hospital emergency room. Another day, like a maniacal slasher, I grabbed a pair of scissors and sliced jagged hems off the living room drapes. (Wait—you didn’t think I did anything crazy, did you?! I was sick of those window coverings anyway.)

There is something to be said for the Christian philosophy that a marriage is like two becoming one in flesh. And I felt that mine was being excised piece by piece. Then during all of this, my father was diagnosed with cancer. Without hesitation, I moved to New York for his treatment, expecting a full recovery. But in four short months, he was gone. My Daddy, whose critical nature couldn’t help but point out the cold ashes in my fireplace when he visited, but who had also finally admitted “I am proud of you,” when faced with my tearful query only a year before.

I tried to avoid the emptiness of Altadena by staying in New York a while longer. When I finally returned west, I was a single, female homeowner. Rather than sell, I had paid my ex for the privilege of remaining in that house in the foothills.

Then a couple of years after my divorce, I met Mario.

Mario’s visits rekindled my interest in my home. After leaving my house the first time, he told me he sat in his car at the top of Lake Avenue, taking in the urban lights below, and laughed to himself: “Altadena? Where in the heck is Altadena?!”

We hosted his sister and several friends at a backyard dinner once, where Mario grilled chicken, salmon and fresh vegetables. I selected the lower hanging oranges from my tree, taking time to joyfully administer a squeeze and aroma test to each one.

“I love seeing you enjoy your home, Ashton,” he shared after our guests departed.

Then suddenly and unexpectedly, before we could celebrate our fourth anniversary as a couple, Mario passed away. Time devolved into a confusion of tears, fast food and Hulu. Getting dressed? Going out? WTF for?

Thankfully, I soon discovered a thing called storytelling for adults. After attending one performance, I knew this was for me. My joy in creative writing, dormant since high school, returned. I was energized: writing, examining my life through humor and pathos and sharing it all as a real member of the Altadena arts community. I spent nights on stage in theaters, coffee shops and bookstores. I even learned what a “dive bar” was when I found myself booked at a joint that boasted $3 beers!

But when the Covid-19 pandemia struck, in-person gigs dried up. The storytelling community soon transitioned online, but the magic of Zoom gave me too much license to half-step: I’d sit at the laptop in wig and lipstick, with my signature pashmina tied smartly over my shoulders and only a towel draped over my lap. After the 90-minute show, I was back in bed or sprawled on the couch bingeing reruns of Special Victims Unit.

My father had admonished me decades before: “Some people eat to live. You live to eat.” At the time, I was so offended and hurt, I didn’t speak to him for weeks. But now, pummeled by previous years of grief, without Mario and feeling totally isolated, I couldn’t find value in life. But there was no way I could actively end it all, no way I could formulate an actual plan.

I wondered, “What if I just ate and ate and sat and sat…”

This was clinical depression.

After months of physical symptoms that I knew were warnings, I reluctantly dragged myself to the doctor but in my shame, told him as little as possible. He ordered blood work and an abdominal ultrasound, but I was too weak to get myself to the lab. Only by God’s plan, two of my best friends had become my housemates only months before. They got me to the ER before the diabetic coma could end me.

Four weeks of hospitalization later, including two weeks of dialysis, test results revealed that my once-failing kidneys had resumed their job. I could hear the technician announce to the entire room, “We hardly ever see this happen. It’s like a miracle!”

I had almost died in that house, but I’d been granted more time.

On January 7, 2025, there was no time. I learned of the fire in Eaton Canyon at around 6 that evening, while in an important Zoom meeting with members of my writing group. Having been through the Station Fire sixteen years before, I had confidence in the county’s warning systems and just kept an eye and ear tuned for calls and texts from the fire and sheriff’s departments.

Still, I had a couple of fresh tee-shirts ready in case we had to evacuate for a few nights, like last time. My housemate Theresa went in for a nap, but I had already cautioned her to be ready (“Make sure you have your keys and wallet!”), just in case.

Around 3:15 in the morning, a flashing red light zoomed past the front window and some garbled commands blared.

“This is it!” I exclaimed, grabbing my bag and heading to the door.

I continued to watch through the kitchen window. I swore I could count the tiny silhouettes of men fighting their way up the mountain near Eaton Canyon, more than three miles away. At least 15 minutes dragged along, time testing my composure. What good would it do to add hysterics to the glowing embers I saw fly by? “How’s that key hunt coming?”

Finally, we were heading to the driveway. A couple of burning floaters danced over to my car windshield. I casually brushed another from my jacket sleeve.

We escaped and landed safely at the apartment of Theresa’s sister, 10 miles away.

Of the 13 homes on my block, two were left standing. But mine was not one of those. I said a prayer of thanks for the young couple on the corner who had been our neighbors for only a year and had a new baby. Their house had been spared. The next time I saw my property was in a photo of my housemate standing amidst the rubble, dressed in full-on hazmat attire. Every fruit tree, every metal sculpture, all flooring and walls were gone.

When I finally made my way up the hill to snap some pics for my insurance company, I only felt a calm ambivalence.

The Eaton fire destroyed or damaged nearly half of the Black households in Altadena, as it razed more than 9,400 structures.

Investigations in the wake of the fire have already raised questions about why those who lived in west Altadena, an area with many Black residents, received emergency evacuation orders after 3 AM, hours later than in neighborhoods a few blocks to the east, resulting in chaotic late-night evacuations. All 17 people who died in the Eaton Fire lived west of Lake Avenue in Altadena, a Los Angeles Times investigation found. Local officials subsequently ordered a formal outside review of how emergency alerts functioned during the fires.

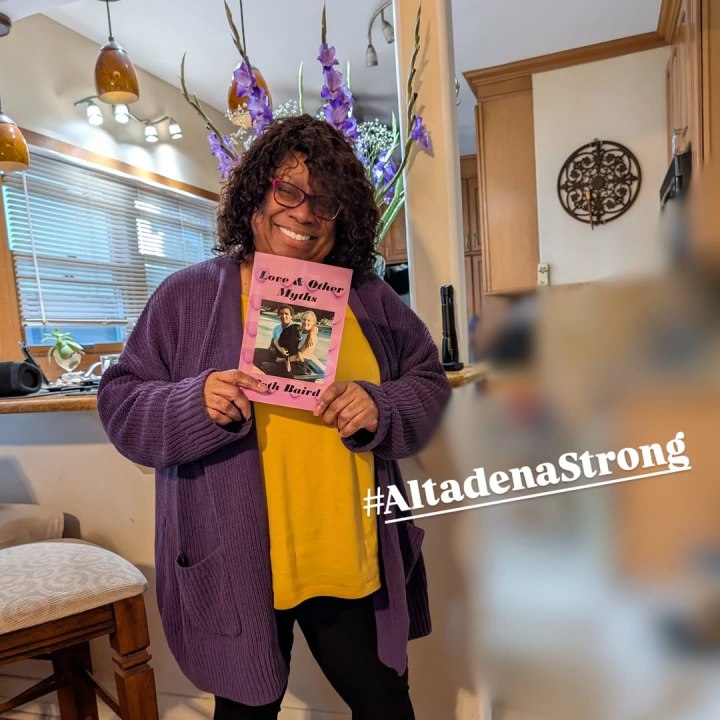

#AltadenaStrong #AltadenaIsNotForSale #Rebuild #BlackGenerationWealth

Just a few of the hashtags that made the rounds on social media.

But may I share with you? I am over 65 years old. I never did have a child. My house was not one of the multi-generational pieces of Black Altadena history. More than half of my years in that house in the foothills were…let me just say it: a misery.

My house in the foothills had experienced three brush fires (that I knew of) and I had been there for two.

Am I actually…let me just say it: relieved to be free?

Do I really want to spend more time on a rebuild that my retired, storyteller/writer ass will doubtless be priced out of inhabiting?

When I think of what I’ve truly lost, I’m haunted by the bright blue box that held my brother’s ashes, which journeyed in my suitcase from New York City the previous year, and which I had not yet deposited in a metal urn. I picture my mother’s diary and her last handwritten letter to me, folded within the pages of that journal since 1992. I dream of the memorial locket that Mario’s daughter gifted me, dangling on a silver chain alongside Mario’s “Jesus fish.”

These items, these memories, can never be “rebuilt.”

“You’re so calm!” “You’re so strong!” people exclaim to my smiling, Strong-Black-Woman face. They don’t know that, had I not just been made aware of my people’s legacy of home ownership in The Dena, I’d have no problem walking away from that burnt-out mess of bad memories and shaking the ash from my sandals.

But can I so easily brush off the legacies of my trailblazer friend, Tecora, and the neighbor who was forced to use a white, surrogate buyer to front for her? Like many Black Americans, the choices I make are often not for me alone but ripple through my whole community and reach back to those who came before.

Quick and final sale? Or slow rebuild? I was terrified of making the wrong decision. And it was tearing my heart into tattered strips, just like those long-ago living room drapes.

I’d been apartment hunting and showed my BFF a photo of my favorite so far: an apartment planted in the pavements of Downtown L.Á. With no holes in the bathroom floor. Absolutely no deferred maintenance.

Willy pointed at the photo: “What mountains are those way in the distance?”

“I dunno.” But I Googled it later.

And tonight, hugging myself in my small, one-bedroom flat, I’m treated to a peekaboo view of urban lights glowing from the centerpiece of City Hall, this time in the foreground—my present. But visible in the background—as in my past—still rise the purple/blue hues of the San Gabriels.

Will I decide to go back? It’s only a one-year lease. There’s time.

Ashton would like to take this opportunity to acknowledge with love and gratitude some of the groups whose generosity helped make her soft landing possible:

GoFundMe organized by dear friends in the storytelling community. And everyone who contributed!

Women Who Submit fundraiser for its members who lost their homes.

Artists Standing Strong Together (ASST) Storyteller Relief Fund

Mobile Data Mag, Jesse Tovar, Editor

Faith Community Fellowship, Kenneth Smith, Pastor

Kairos Community Ventures, Eaton Fire Relief. Via Pastor Brad Arnold, Pasadena Church

Black Skeptics of LA, BSLA RR Microgrants

And every family member, friend, friend of a friend, and anonymous donor who so kindly helped me.