I should have been writing. But writers will do anything to avoid the keys. Laundry. Sweeping. “Research” aka “scrolling” or going to a grocery store to get stuff they don’t need.

As soon as I entered, bushels of peaches begged to be touched, hailing from their famed state of Georgia. These large, almost perfect yellow and reddish globes felt different from the ones in California. Heavy, they smelled sweeter and with less fur, softer to the touch. I could almost taste the pie I planned to bake.

But I didn’t make a pie. I ate the peach raw on the street, remembering the last time I saw poet Lynn Manning.

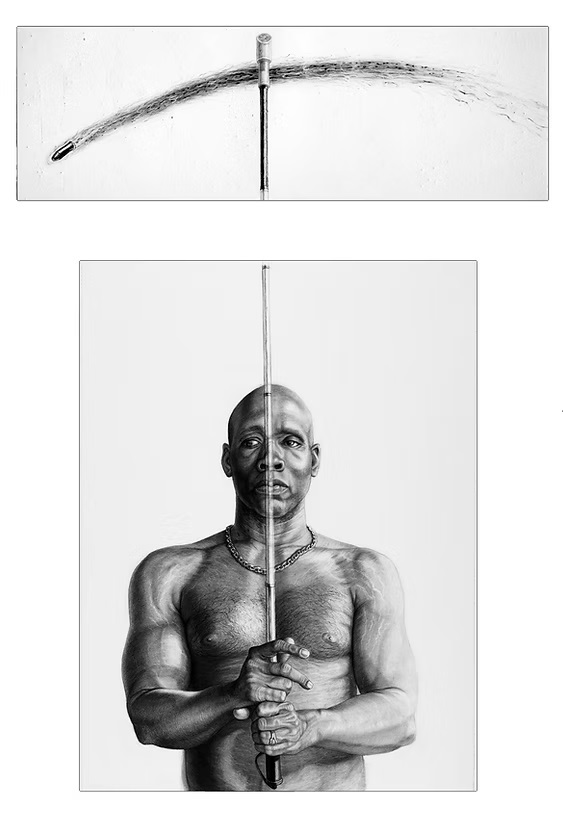

Lynn was a specimen. A poetic extraordinaire, whose chiseled physique echoed his taut, striped-down prose which cut like a blade halving fruit.

I’d known Lynn ever since our poetry days in the 1990s, a juicy time when poetry blazed across L.Á. feeding venues all over the city. From East L.Á. to the valley, South Central to the beach, you couldn’t step into a coffee shop without seeing a reading with people standing 3 or 4 deep.

This was the dawn of L.Á.’s renaissance, an era where poets and rap artists mixed. Places like “The Good Life,” showcased groups like Pharcyde with poetry-centric lyrics, like their signature piece “Passing Me By.” These were times when 20 poets would read at a time, before readings competed with noisy machines and the commodification of coffee closed great mom-and-pop shops, with a serialized reincarnation called Starbucks.

“I’ll raise your caramel macchiato for “Coolio’s Gangsta Paradise, please!”

Lynn and I sprang out of harrowing times. A time of earthquakes, OJ chases, policemen beating folks silly, a fiery riot that charcoaled whole blocks and Lyle and Eric Menedez shooting both parents without ever blinking.

A haven for the seedy, L.Á. has always been sketchy. A playground for Hillside Stranglers stalking Hollywood Hills, a place where poets like Wanda Coleman hung out with criminals like Charles Manson, a place so warm yet so violent, there was a reason it was called the Wild Wild West and before that, Hell Town, where the bartenders wore ear necklaces around necks broadcasting all the people they slaughtered. Despite its huge size, L.Á. was layered and unique, with multiple nooks and crannies and different communities of all shapes. Big with an intricate physique, L.Á. from mountains to coasts, was the perfect place for natives like Lynn and I to roam.

Lynn’s roaming days ended after a tragic event in a Hollywood bar when a bullet to the head left him flattened and damn near dead, severing an optic nerve and ending his career as a painter.

But this didn’t kill him. L.Á.’s the king of second acts. Lynn pivoted and kept moving, like a ninja blocking kicks and manifested a new line of work.

“In the absence of that vastness, that visual feast, I came to recognize the overwhelming distraction that sight had been. I had never noticed that sound moves the way it does, or feels the way it does.” — from “Weights” a play by Lynn Manning

Like any true Angeleño, Lynne found another expressive form. So, instead of painting pictures, Lynne painted images with words, becoming one of L.Á.’s most sought-after poets.

Handsome, six-foot-two, with wide, front-door shoulders, Lynn excelled physically and on the page, flexing writing chops and abs. Even after being blinded, he never let it hold him back. A black belt in Judo, he competed in the Paralympics winning accolades all over the world.

Exuding a Black Los Ángeles maleness, a kind of pimp-Daddy-cool, Lynn’s resonant voice and healthy dose of athleticism and obvious strength, made any thoughts of disability fade away. Even the occasional arm required to lead him onto unknown stages evaporated as soon as Lynn moved his lips.

I remember how crowds exploded when Lynn held a microphone in his fist and everyone in the audience became Braille inhaling his fingers. We ran into each other all over town, attending many of the same venues; Highways, The World Stage, Beyond Baroque, Highland Grounds, coffee houses and bookstores like Midnight Special and Book Soup, places that encouraged poets to perform and share the word.

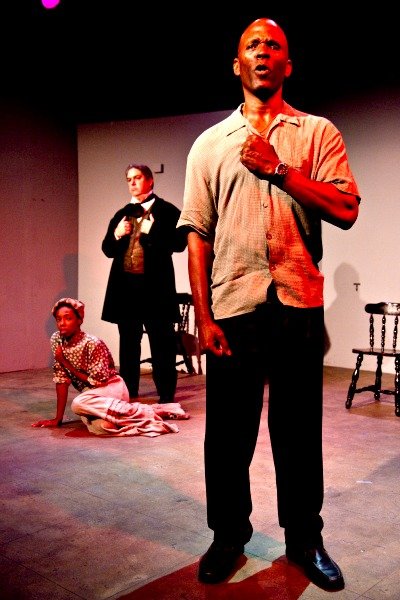

Lynn caught the acting bug and became enamored by live performance, and segued poetry into writing and performing plays, co-founding the Watts Village Theater Company, the only such venue in that part of town.

His autobiographical play “Weights,” examines a black man’s trauma and triumph, and received international acclaim.

Outside the “powerhouse of playwright development,” according to Dramatist Magazine, my last encounter with Lynne was at the Skylight Theater on Vermont. It was after one of his productions, a show that challenged the role of Dr. Marion Sims, the so-called Father of Gynecology. Sims “experimented” on slaves in the development of specialized tools, creating the specula, an instrument forged from spoons, which helped reveal a female’s fleshy core.

This play wrangled with the rights of doctors whose scientific experiments furthered the greater good, against the backdrop of patients who didn’t provide consent. Sims operated on enslaved black women without anesthesia, cutting them open and stitching them back up with wire while other men held them down.

I can still hear the play’s pivotal line: “Yeah, but didn’t Sims help?”

This was Lynn in a nutshell, going for the jugular with hyperbolic verbs. Passionate, and confrontational, Lynn morphed the political into personal worlds, allowing audiences to figure it out for themselves.

That was the last time I saw him. After the show, while driving Mom home. I saw Lynn tapping his way to a bus stop down the street, swinging his cane like a magic wand. Instead of a man needing aid, Lynn held his cane like a prop, something he tapped or clutched like Bruce Lee. Lynn walked calmly, even though the navigation seemed tough, street vendors blocking walkways, trash and abandoned boxes, a symphony of agitated drivers pressing horns, homeless folks bedded down on sidewalks. It was late, almost midnight, and very dark outside, but this blind man seemed unfettered by this, existing within the curve of a permanently blackened globe.

“Hey, Lynn,” I screamed. “It’s Pam Ward, need a ride?”

Lynn turned toward my voice and trotted in the street to my car. Mom opened the back door and Lynn sat behind Mom’s head, smiling at his fortunate luck. That’s how L.Á. is. If you’re carless, rides feel like gold, a welcome mat of metal, a portable home, a Lotto ticket sheltering you from the cold. I recalled my own days at bus stops, seeing a friend was like striking it rich, like a bowling ball hitting all your pens.

As I drove, Lynne comfortably leaned back in the seat saying, “I smell peaches.”

“Yes,” I said. “Have some.”

Mom gave Lynn the bag and he picked two globes, holding the furry skin to his nose.

“Ah,” he said. “These smell good.”

I didn’t know if they were good or not. I bought them from the 99-cent store a few hours earlier. One bag for only a buck.

I dropped Lynne in Koreatown, near the reformatory where he lived as a kid. I asked him how he knew how to get around, “Smell,” he said. “And the math of counting steps. Two rights and a left.” He thanked me, slipped two pieces of fruit into his jacket, and after a quick tap was at his front door.

A few months later, I heard Lynne was gone. But Lynn inspired a generation and showed us how to work with what we had. How to pivot. How to document the moment, like holding a peach in your palm. How to follow the lens of your nose, wherever it leads, ready to gnaw into life whether you’re ready or not, catching whatever it throws.

Lynn Manning, a Los Angeles Star

shot in bar, Lynn turned

a nightmare into art

turned blindness into gifts

that could be played out on stage

turned rage into pages

and pages and pages of riffs

cuz y’all know brothaman was prolific!

this black man, this beacon

who tapped melodies on streets

with only a stick and a seeing eye dog soul

turned tragedy into love stories

about agony or tongue kiss nights

cuz Lord knows, the brotha was fine.

So don’t cry for Lynn Manning

don’t even act that he’s gone

cuz when a poet goes

he lives on and on in his work

lives in constants, hyperbolic verbs

shining from computer screens

All the way to Kingdom come

cuz when a poet goes

he leaves sign posts

high-fives from the sky

throwing poetic gang signs

from Jupiter or Mars

showing us the Dead Sea

scrolls of Hollywood & Watts

or the Romeos plotting on Melrose.

cuz when a poet goes

another strobe light

blasts the sky

Glitters across galaxies

like a blind man’s

fluorescent stick.

reading the arc of

a woman’s spine.

tap tap taping

his Morse Code

across keyboard street

cuz when a poet goes

he becomes lamppost

a flashlight for all to see

becomes beacon

North star on dark nights

bulging like Braille does

embossing us, scattin’

bumpy rhythms on sacred sky

teaching us all how to shine.