In her latest collection of poetry, Grasping at this Planet Just to Believe: Poetry a Day Over a Decade of Ramadans (Write Large Press, 2024), Tanzila Ahmed weaves a decade-long tapestry of introspection, resilience, and building community. This poetry collection stands not only as a testament to her healing and to orienting her faith after a deep loss but also as a chronicle of a vibrant online community she nurtured—a sanctuary for Muslims, Muslimish, and allies to gather and write during the holy month of Ramadan.

For over ten years, Ahmed established and curated the Poetry-A-Day for Ramadan initiative, providing a digital haven where fasting writers from around the globe could share their reflections, struggles, and joys. “I started the group right after my mom died,” Ahmed reflected, recalling the genesis of this virtual gathering to create a sense of family and belonging to cope with the loss of such an integral figure to her sense of self and sense of being Muslim in the world. “In 2011, I did one month of poetry writing for Ramadan. Then when I told some friends, they said, ‘Oh, I wanna do this also.’ And soon, we had a group wanting to write together.”

Utilizing Facebook’s platform, Ahmed forged a supportive community amidst heightened surveillance and Islamophobia. “At the time, we were being super surveilled. So, ensuring people were real online was important to me,” she explained. With meticulous care, she curated an environment where participants could freely share their poetry, navigate their spiritual journeys, and confront the socio-political challenges faced by Muslim communities worldwide. And we, who were participants in this community, felt the care she took.

Ahmed is passionate about spaces that are built on a spirit of welcome. “I just wanted a space where we could come as we are and have conversations. We want to be able to write about our struggles without the fear of being judged by the ‘Haram Police.’ When you’re under constant watch and judgment, both by white supremacy and by traditional imams, then you just don’t have the space to explore and have conversations.”

Born into a Bangladeshi American family, Ahmed’s artistic journey began with exploring her cultural heritage and identity. Her research in adulthood was different from her Islamic training as a child, which emphasized reverence over questions, but instead explored Islamic mysticism, art, and literature. In a community of Muslim and Muslimish, Ahmed developed a deep-seated appreciation for storytelling within the Muslim cultural tradition, which became the self-built foundation for her visual art, poetry, and essays.

For years, Ahmed has been at the head of experimental and progressive movements by young Muslims/Muslimish. As she developed her voice, the tragic loss of her mother focused her to poetry and visual art. “I started doing visual art after my mom died,” she shared. “We were cleaning out her stuff, and I found all this ephemera—things my [mom] had saved. So I started making art out of what I found.” From this online community, came the warmth of healing.

One series of paintings Ahmed finished reflects the Islamic belief that the moon will split on Judgment Day. “Recently, I’ve been doing a painting that refers to the Islamic belief that the moon will split in two on the day of Judgment. This is one of the signs of the apocalypse,” she explained. Another set depicts a line about planting a sapling even in the face of impending doom, a testament to hope. “You know where it says if it’s like the end of days and you still have a sapling in your hand? If you plant the sapling, you’ll still gain from it. So I did another painting that was based on that.”

Ahmed’s work isn’t just about the self in relation to faith and healing. Her writing and art, such as the Poetry-A-Day for Ramadan writing space, her podcast series Good Muslim/Bad Muslim, and the Muslim Valentine card series that connects friends, are communal endeavors that bridge cultural heritage with contemporary challenges and celebrates the diverse tapestry of Muslim identity in America.

Ahmed’s poetry book, Grasping at This Planet Just to Believe, reflects the communal processing of spirituality, grief, and political turmoil during this fasting month. “In the book…you’re able to match the poems with the year’s politics,” Ahmed explained.

One striking aspect of the book is how it mirrors the emotional and spiritual journey of Ramadan. “The first week of Ramadan is filled with excitement. And then, there’s always the middle, where people are just tired and hungry. That is the struggle…And then, towards the end, Ramadan is always a joyous feeling. This pattern happens throughout many Ramadans, and you can see it in the poems,” Ahmed observed.

Despite her emphasis on community as a core theme in her poetry, a poignant recurring motif in the collection is nature, particularly flowers. Jacaranda flowers, flourishing amid an urban harshness, appear in many of her poems.

Evenings are scented intoxicatingly

from the white night-blooming stars.

The romance of spring

gets smothered in the morning gloom.

In her poem “Jacarandas and Jasmines,” the scent of flowers is fleeting. When daylight comes, it is consumed by the grief of morning and awareness of her loss. In the poem, “Spring in My Dreams,” Ahmed writes:

I dreamt the jacarandas were in bloom last night.

I am charmed by the love letters in my nightmares.

The petals dissolved into vermin in outstretched fingers.

The longer lines of the poem, the reach of her hand, and the transformation of vibrant purple flowers into vermin evoke a deep sense of longing tainted by grief. This unsettling image captures heartache, juxtaposed against the lush warmth of a flower, now a symbol of gnawing sorrow.

This melancholia is ever present in her poems. During these Ramadans, the new moon is a portal to utter vulnerability. How else can we pray if we are not completely receptive? And to be open means that wounds are also bared. She writes in “Moon,” on the first night of Ramadan, “and she, the crescent moon, smiles slyly off-kilter.” Ahmed personifies the moon, as in ancient traditions, and marks it as “she is to be our witness.” And so the poems enter into a month of fasting from food and mother. “Because the ultimate fast, the most difficult sacrifice is/to live without your mother in it.”

Ahmed’s mother, a north star in her life, and as the children of immigrants, there is an unspoken understanding that our parents are our countries, the first place of belonging for us in which we feel whole and not fragmented, is present in all Ahmed’s poems, even those not about her mother. But more than the soft suffering of grief, Grasping at This Planet Just to Believe reflects Ahmed’s evolution, a self-making process that relearns faith and her relationship with God and the community. “In the early years, I was healing from the grief of losing my mother.” This healing journey is mapped out in the lunar cycle-themed structure of her collection, aligning the phases of the moon with the ebb and flow of emotions experienced during Ramadan.

Ahmed’s creative output is deeply entwined with her activism. Her projects—from poetry and visual art to podcasts—reside at the intersection of being American, Muslim, and Brown. Through her art, she addresses social justice issues and amplifies marginalized voices within the Muslim community. Her poetry, in particular, acts as a collective work-through of societal challenges, providing a platform for resistance and solidarity.

“One…other thing…I think about is that we did have non-Muslims in the [community] space, they were people I considered allies of the Muslim community, and they were the ones…fighting for social justice. And then we also had a lot of queer people in this space. And I think, like so often, queer Muslims are pushed out of conventional Muslim spaces. They wanted a space where all kinds of people were welcome. Like I wasn’t welcome in the mosque space. I wasn’t conservative enough for conservatives, but I felt like there was a social justice part of Islam that I was practicing. I didn’t have access to that growing up, and now I feel like there’s access to so many people who are…Muslim and practicing social justice…It was a poetic Muslimish people that could write poems and explore there…learn together through poetry and share space.”

Ahmed is very open with conversations about faith. “Muslim-ish” is an especially important third space for her to create. It is where one can ask questions about faith, Islam, religion and religious rituals, knowing that they will not be banished from the community. Her poetry glows with moments of feeling connected to the divine through love or the adoration of nature, and at other times, she is closed off from those intimate tendrils that connect her to faith. In the poem, “Marble Mouthed Lip Synch,” she stretches out again to give a visual to this feeling of disruption from community and faith:

The suras roll around like marbles in my mouth

but spill out like broken, shattered teeth like in a bad dream

falling on dusty prayer mats from right to left

scattered between pauses and emptiness and blankness.

It is these fissures in the marble of practicing faith that add vulnerability and give her heart the breathing space needed to cultivate one’s degree and level of faith and religiosity. For Ahmed, teetering on the edge of faith and feeling the beauty of it is where for her, she marks her faith. It is a constant questioning of not only faith but of belonging. Will these prayers stitch back the ruptures of losing her mother? Will these holy words entwine her to love, or are they insufficient? These are the profound questions she grapples with in this collection.

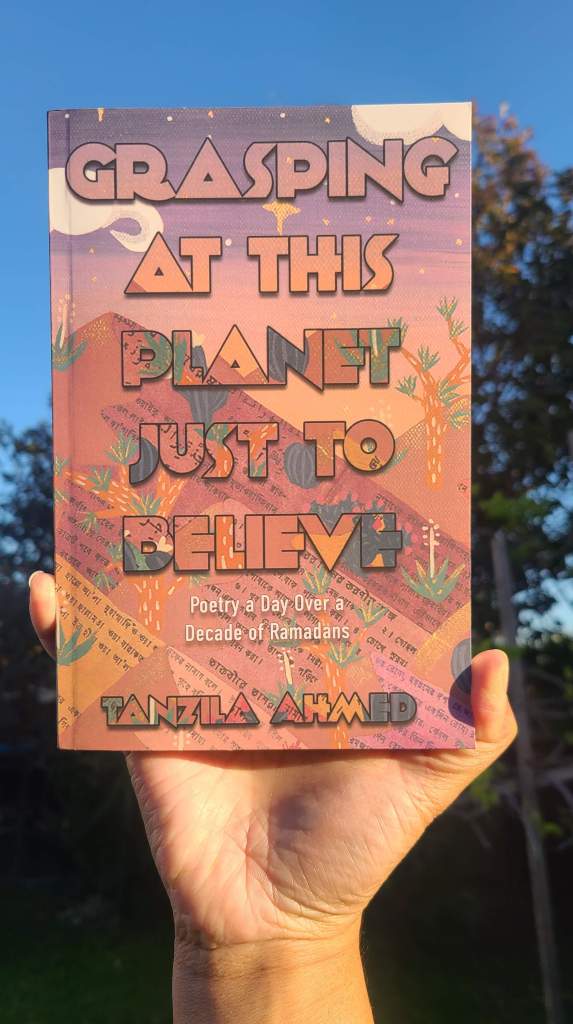

The cover of Ahmed’s poetry book is a collage that features pages from Bengali textbooks teaching Arabic, sourced from her father’s collection. “These are out of a [text]book in Bengali teaching Islamic text in Arabic.” The textbooks were for a mosque her father had been developing in Ontario. But the mosque closed for unknown reasons, and Ahmed’s father held onto the textbooks. Sacred texts cannot be thrown out. So, in this way, the books were stored in limbo for decades until Ahmed snuck them out to make art.

The artwork symbolizes Ahmed blending her Bangladeshi roots with her life in California, where cacti and Joshua trees represent resilience and adaptation. To Ahmed, this collage is a metaphor for the immigrant experience, combining these elements of the first generation’s attempt at creating an inclusive space for themselves with the present space where the second-generation immigrant seems to find roots and connection to the land—this fusion of unbelonging and belonging creates a cohesive and meaningful whole in her cover art.

The cover of Ahmed’s book, the material used, and the imagery, are symbolic of a family’s immigrant history. The first generation migrated here and tried to create a safe space and community to continue cultural and religious traditions. When this pioneer generation is unable to create that space, the next generation takes pieces of that desired wholeness and recreates it to find solidarity and self-expression.

For Ahmed, she sneaks into her parents’ storages and archives and returns with shreds of material to build her Muslimish Ummah. In “Post Modern Pray” she weaves in these memories of contemporary Muslim American households and how we practice with replicas and symbols of Islam. Rather than mosques, sometimes all we have are photos of mosques or etchings of domes and minarets at storefront mosques to recreate this sacred space that stems from our memories of such places:

The static-y call of azaan

echoing out the

plastic gold painted mosque

resting on the coffee table –

We have a sense of a miniaturized and displaced mosque and call to prayer, portable and made with cheap material. When she wrote these poems, Ahmed was aware of her audience, so she wrote to her ummah. “In this space, the listener, the audience you’re writing for, is clear. The writing becomes more intimate in this safe space,” Ahmed observed. This intimacy and authenticity are at the heart of her work. She can speak freely, and boast of practicing faith in marginal spaces and in motion; even breaking her fast is sometimes done in the car, as she writes in “Iftar Streets.”

I should pull over; I think to myself

but in a city where God is invoked in cars, primarily

the wide sky is the dome of my mosque

these roads my prayer rug.

And for us, Muslims in the diaspora, raised in countries that are secular or sometimes hostile to our presence, the dome of the blue sky becomes the mosque in which we pray.

“The poems are the essence of what we experienced together during many Ramadans. I wanted to hold on to the feeling I had at the moment. I like the authenticity of capturing a moment, a sentiment of time for us as Muslim Americans in these poems.” In this constellation of multiple variants of Muslimness/Muslimish/and allies, the poems and the Poetry-A-Day [for] Ramadan space encompass the landscape of that place of belonging, a place of welcome, and a place of advocacy for social justice issues. We see this in the poem “How We Love.” Ahmed writes about being awakened by her non-Muslim friend for suhoor, the meal before sunrise. In her sleepiness, she conflates her friend’s voice with her mother’s and is transported back to “bowls of frosted flakes” and a busy dining room table with her mother fussing over her family.

I peek eyes open

to see my non-Muslim BFF houseguest

with a flashlight in one hand

a jug of water in another

‘It’s time to eat!

I set my alarm for you!’

This tenderness between friends during the rigor of Ramadan fasting creates a new kind of family and community for Ahmed. The book documents the evolution of individual and common experiences and moves beyond being a collection of poems; it signifies the strength and fortitude of a community bound by faith, creativity, and the shared journey of fasting and reflection.

It encapsulates a decade of poetic exploration and bonding, reflecting the dynamic interplay between personal grief, spiritual growth, and social activism. Through these ten years, Ahmed has not only chronicled the highs and lows of Ramadan but has also provided a platform for others to voice their stories and struggles.

“This book is…like one puzzle piece of this larger project that I’m doing… All kinds of art projects at this intersection.” In the poem for Palestinian poet, Randa Jarrar, “Making Witchy Duas,” she writes:

Her prayers are infused with the feminization of God

What do you mean you make Allah linguistically feminine?

Ahmed transcends traditional boundaries and brings a feminist breath to the altar of faith. In her poems, many dedicated to fellow poets, friends, and activists, she opens up intimate conversations between those exploring and practicing in their own way and presents a nuanced portrayal of Muslim American identity. Her Muslimish space, Poetry-A-Day for Ramadan, created on the pages of her poetry as well as online and in personal gatherings, is a precipice of faith, traditions, and innovations.

Her commitment to fostering inclusive creative spaces has empowered this circle of artists, writers, filmmakers, activists, and those in the margins, to share their voices and stories authentically. We have fostered friendships and collaborations that have lasted for years and years. Poetry-A-Day for Ramadan was a safe writing home to turn to in a world that saw Muslims as terrorists, as suspect, especially during a month of reflection and transformation. Tanzila Ahmed has given us as a gift, her activism in a bound book.

One thought on “Tanzila Ahmed: A Collage of Art, Poetry, and Community”