Beyond Baroque was my savior. A candle burned at night. I needed it to survive. Once a week, like clockwork, I climbed its chipped, blood-red steps to attend the Wednesday night poetry workshop, the longest on-going one in the city, a refuge, a place to spill my guts on the page and get my much needed dosage of words.

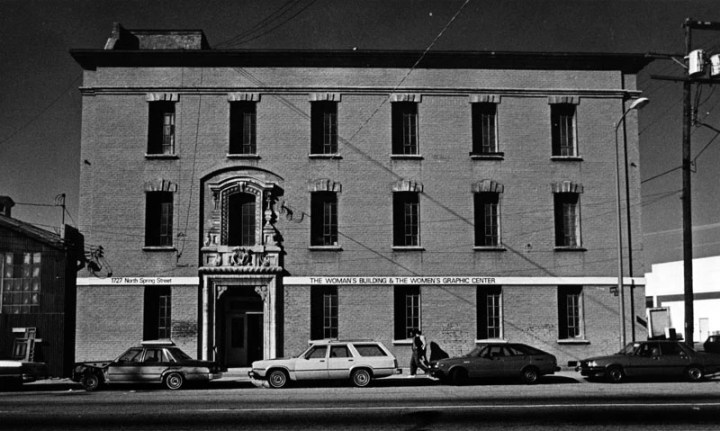

I discovered this seaside oasis while working clear across town at The Woman’s Building Downtown on Spring Street. The Woman’s Building was a hybrid haven for feminist artists, and I interviewed to manage the graphic design center there.

The Woman’s Building seemed like a dream job, a springboard to many endeavors and I cried like a baby when I didn’t get the gig. I was the runner-up. Their failed second pick. So when they hired someone else, I took an ad agency job working at this hideous pristine shack in Beverly Hills. The agency was run by a bunch of pompous pricks, entitled and sexually aggressive.

Everyday I was greeted with a sink full of their dirty dishes which they wanted me to wash before starting my duties. I mean, come on, who can’t wash their own mug, and worse, these assholes winked while I scrubbed saying stuff like, “Boy, what a sudsy beauty.”

But after two weeks at the dishwashing factory, The Woman’s Building phoned again asking if I still wanted the gig. Apparently, the hire had grossly misrepresented herself and was unceremoniously let go.

To be honest, I misrepresented myself too. The Woman’s Building job meant managing women ten years older, so I masqueraded my youth by sporting vintage, thrift shop suits, glasses and a schoolmarmish bun. What a clash from my former UCLA black student reporter days, where I wore camouflage pants, wild hair and jeans, interviewing men like Black Panther Eldridge Cleaver, the most arrogant, interesting man I’d ever known, with eyes that could suck a girl dry.

But the Woman’s Building was ripe and oozing with juice. The entire place thrived. It was a living and breathing thing. An experiment in feminist, communal artists working in real time, and everyone washed their own plates. The place was co-created by graphic artist Sheila De Bretteville, who designed a public piece on Broadway honoring Biddy Mason, the first black woman to own land in L.Á. With these ingredients, everyday at work was amazing.

I worked at the Woman’s Building two and half years straight, dropped a baby and never missed a beat. I learned about birthrights, letterpress printing, how to advocate during delivery and they even let me bring my baby to work with me. I’d walk down the aisle nursing my newborn Mari or place her in her crib behind my desk and they even put her in one of their movies.

For a young, troubled mother like me, without real direction, this place was a godsend. I’ve never experienced anything so nurturing, so vibrant, and so intense and I’ve never seen anything like it since. The whole building throbbed, ebbing and flowing like blood. Even the building, a regal, rust-tone structure on Spring, proudly beckoned to you from the street.

It was an odyssey, an oasis, with tasty vegan potlucks and writing salons or art workshops where I met dozens of folks including Anise Nin’s husband. Fitness classes existed in the gallery and we’d work out with Terry Wolverton playing Sam & Dave’s “Hold on I’m Coming,” doing crunches while watching the artwork on the wall, displaying a 1987 tribute, “Viva la Vida: An Homage to Frida Kahlo.”

I’d never heard of Frida Kahlo before. But the Woman’s Building enlightened me and I bought her biography by Hayden Herrera, one of the most memorable works I’ve ever read. Everyone in L.Á. rode the Frida-fanatic wave. Her L.Á. explosion put Frida back on the map. She lived on keychains, on earrings, on T-shirts or drapes and I bought a calendar of her paintings so I could rip the page and frame her work.

As a graphic artist/writer, I couldn’t get enough. Frida’s life story mirrored some of my struggles at home, so reading after her journey made me feel seen. Frida turned travesty into colorful art. She was a 20th Century star, a woman who painted suicides, or butchering her locks, a person Picasso called “the best of all of us.” The Woman’s Building hosted Frida and so many more and my artistic journey surged.

In a mostly boys-run town, the Woman’s Building flexed. It rubbed elbows with MOCA, Self Help Graphics and LAX, the Biltmore and Bonaventure hotels and Carmen Margarita Zapata, considered the First Lady of Hispanic Theater, and founder of the Bilingual Foundation of the Arts.

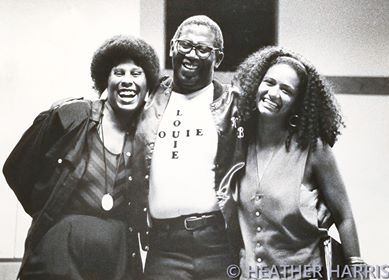

Everyone came to Woman’s Building events or the Woman’s graphic center, their profit making arm where I worked, to get postcards or newsletters done. One day, while working on a flier for a literary event called “Cross Pollination,” Wanda Coleman and Michelle T. Clinton bolted in the door. Black women at the Woman’s Building were too few and far between so seeing these real, downhome black girls, from my mother’s hometown in Watts, I immediately gave them all my attention.

I’d heard of Wanda, I’d seen her perform at UCLA as a student, but we’d never officially met. Wanda had edited the Woman’s Building anthology, “Women for All Seasons,” and I illustrated the cover art. After months of listening to me shit-talk near the coffee machine, my co-worker Linda Lyons encouraged me to submit and I wrote a story about taking care of my great grandmother, entitled “Mama Dear,” and Wanda put it in. She was the first to publish my work.

So when Wanda and Michele told me about their reading at this facility called Beyond Baroque, I really wanted to go. “You’ll love it,” Michele told me, “the poetry workshop is free.” Unsure of the place, I repeated the name, “Beyond broke?” It sounded like a check cashing place. “NO, HO-NEY!” Wanda corrected in her megaphone voice, “BE-YOND BA-RO-KAH!” she enunciated in seasoned diction, “A literary facility near Venice Beach.”

Venice was my ocean. I’d been going since I was a kid. Back in its open, nudist colony days when people paraded and laid buck-ass all day. In those days, I walked with my family, wedging between bodies to get to the shore where people wore nothing but smiles. It didn’t last long. Mayor Bradley shut it down and by the time I entered Uni high the nudists were gone. Now it was a rollerblade haven, an insta-tent, ad hoc mall, where muscle men glistened and brown men hooped and Zboys skated over asphalt selling nickel bags of weed or what they all called “pot.”

Intrigued, I decided to try Beyond Baroque’s class. Because even if it stank, even if the class was full of shit, at least I’d get a whiff of the ocean. As an L.Á. native, I skipped the gridlock flooding the 10 and took Venice Blvd all the way up from Crenshaw. As soon as I crossed Lincoln, Beyond Baroque loomed large. Sitting on the North side of the street, it mimicked a California Mission, the kind of place built to colonize natives. I parked on a gravelly lot, walked across a dry, deadbeat lawn, hiked the steps to a lobby and entered a totally, pitch-black room.

All the walls were painted black. A man wearing an oxygen tank hosted the class. Everyone sat in a circle, a wheel of cold folding chairs. I grabbed the last open seat. Poems were read. People recited then passed around copies. The vibe was serious. Attentive. Low-key yet alert. There was no crosstalk. You could only discuss the work at hand which kept us focused and on topic. The first time, I just listened. The next week, I read my own piece. After that, I rarely missed a class.

Bob Flanagan’s Wednesday night workshop introduced me to a brand new breed. This was Venice, many of these poets had been there for decades, anyone and everyone walked in the door, a blend of old-style hippies and newbies. I met FrancEye (Bukowski’s ex) and often gave her rides. I met David Weinreb and his pizzicato film-noir riffs. I met Viggo Mortenson long before his Lord of the Rings fame where he read tender, urgent, work in monotone-rasps.

Beyond Baroque Literary Arts Foundation was true to its word. It was literary. It was a foundation for writers of various stripes, it housed a theater, a literary library, an upstairs art gallery, and a yard and hosted everything that had to do with writing. From screenwriting, to poetry, to novel writing or performance art, anything a writer needed to sharpen their fangs.

Hordes of L.Á. poets wandered through Beyond Baroque’s door, poets like Scott Wannberg, a ‘hootenanny’ sweetheart, who could make you laugh or gasp. Writers like Exene, Philomena Long and Holly Prado and even New York bards like Frankie Rios. I met SA Griffin there. SA promoted everybody and created wild events and one day he asked me to read. SA put fifteen or twenty-five people on the bill and his reading went way into the night. He had a poetry troupe fondly called Carma Bums, and they’d frohlich or wear costumes or paint their skin and I met Laurel Ann Bogan and Mike Mollet and we’d perform in seedy spots like El Carmen.

For some reason, L.Á.’s racial tension made the poetry scene hot. This was the early 90’s. Rap music was hitting its peak. OJ was a gas tank short of taking his famous Bronco ride and the streets were seconds from riots. Even places like Beverly Hills were hit with hard crime when Eric and Lyle Menendez axed their own parents.

But poetry was thriving. We all did our thing. El Rivera was reading at the Roxy. Christian Elder, (son of Lonnie Elder of “Ceremonies of Dark Old Men” fame) brought the Iguana Cafe to life. I read with RegE of “Please Don’t Take My Air Jordans,” fame and the metaphor-maker Ellen Maybe. Rick Lupert hosted a spot in the Valley and published broadsheets of our work where people like Brandon Constantine blazed the stage.

I drove a bucket but I often gave poets rides. On one run, El Rivera hipped me to a tiny storefront, not far from my pad, a spot created by Jazz Musician Billy Higgins and Poet Kamau Daáood affectionately named The World Stage. A Jazz and performance venue founded to carry on the legacy of the Watts Writers Workshop.

The Stage (called by regulars) hosted their own Wednesday poetry evenings called the Ananzi Writers Workshop. The first half included a workshop where people read on stage while others critiqued their work, and crosstalk was actually encouraged. The second was a featured poet and then a boisterous open reading which lasted until eleven o’clock. Unlike Beyond Baroque, The Stage was loud, cheerful yet strong and so crowded you fought to get in. The Stage had a no bullshit policy and kept a sign on the podium to enforce this fact and every Wednesday night it was fire. I met greats like Ojenke, a member of the famous Watts Writers Workshop, Peter Harris, current host V. Kali, along with poets Jaja Zainabu, Wendy James, Shonda Buchanon, Ruth Fomon and way to many other significant poets to name.

Gradually, I skipped Beyond Baroque, to hit The World Stage and that’s where I met Eric Priestley. Eric was an O.G. A spawn of the Watts Writer Workshop in the sixties, started when “On the Waterfront,” writer Budd Schulberg posted a flier on a door, announcing a workshop. Maybe Budd was motivated by the ‘65 riots. Maybe he was making amends for naming-names during the McCarthy era. Whatever the reason, Budd helped many; including Ojenke, the best poet alive who was friends with Bob Marley. Or Louise Meriwether, author of Daddy Was A Numbers Runner, the best book I read as a kid. Or Johnnie Scott who went to Harvard from Watts and Watts Prophet founder Amde who blended words into verbal tones and Quincy Troupe who started an offshoot in Harlem and wrote the seminal tome on Miles Davis.

But this wasn’t the 60’s. This was thirty years later. By this time, Steve Jobs had entered the game. Graphics weren’t done on mainframes anymore. And even lay people like me joined the party. As the Women’s Building’s typesetting mainframe died a slow death, I left and bought a Mac Plus myself and started my own graphic design business. This was just after the Rodney King beating and L.Á. had enough, and after “the verdict” it violently burned to the ground.

With L.Á. in turmoil, my clients refused to come to my neighborhood for work. Bored, I decided to write what I saw on my porch, scribbling a novel longhand while my city was looted. I called the novel, Want Some Get Some, something we said on the playground, just before going to blows. It sat in a shoebox underneath my mattress for years until my cousin offered to type it up. Suddenly, and with the help of Steve Job’s machine, I could vividly see my work on a screen.

And that’s how my poetry slowly morphed into prose. Eric Priestley immediately took me under his wing. I found an agent which led to Kensington giving me a two-book deal. I didn’t have another novel but I told them I did. So, I turned a short story I had into a second piece of work, based on my mother’s criminal knowledge in the funeral circuit and the horrible results of the McMartin Preschool trial. I called this novel “Bad Girls Burn Slow,” and one year later it was published.

But I was still a poet at heart. I still read and loved listening to the new voices, enjoying new poets while remembering ones that I lost. Merelene Murphy. Yvonne de la Vega. Amy Uyematsu and Michelle Serros. Eric Priestely. John Thomas, Scott Wannberg and Linda Albertino and so, so many more.

Poetry keeps me from falling. Poetry props me up. Whether it was Lisa Bonet’s spot where incense christened our heads or Jaha and Nailah soothing us with song. We’d poet in Long Beach, Chinatown and East L.Á. and even ran up to the Bay. We read in dumps, we read if only one person showed up. We’d sit in seats where some poets droned on for decades or saw the electrified performances of famed HollyWatts, the unstoppable Roger Gueneaur Smith.

We read and read and read and read and read all night long. Performing our best or ever our ‘not good yet,’ trying to tap the pulse that surged in our veins. We read for peanuts, or only a few drops of caffeine, but mostly we read to hear or be seen. We’d bleed our tiny hearts out with words, reading about unrequited love or not being able to pay rent, or going hungry, like Dr. Mongo did, a homeless poet who lived in Downtown L.Á. and whose poetry still echoes the street.

We lived in chapbooks, made from our very own small meager hands like Blue Satellite or Picasso’s Mistress, or Sic and I made lots of books for my friends and started my own poetry press called “Short Dress Press.” I followed my own mantra. I never asked permission. I lived by the rule of “publish yourself.” I didn’t wait to be validated by others. Nor did I wait to be asked to read at venues. I’d often barge in and ask. I was shameless and I didn’t care. Michele T. Clinton helped us validate and define all our efforts by saying, “Don’t wait for someone to bestow a writer title on you, if you write, call yourselves writers.”

My first book was a self-published, hand stapled, Xerox job, consisting of a Polaroid taken by my daughter Hana on orange 5×5 paper on a CD sized booklet with the slang phrase, “Jacked Up.” Poet Lynne Bronstein reviewed it and wrote the back panel blurb and for this, I remain forever grateful. Many of us made these gems and hoarded others work like precious California golden nuggets.

Poetry saved me. It totally changed my life. Instead of wallowing, or committing an audacious crime, I heard Marisela Norte turning bus language into art or Paul Calderon doing “Drummerman,” at The Stage until the veins grew over his face. Poetry gave many of us an outlet, a place to blow off some steam, a place to relax in, to create or passionately vent, providing an outing we looked forward to daily.

We did everything. We used what we had. We let technology, music and poetry mix. There was the Electronic Cafe in Santa Monica where they projected our poetry readings into other states. There was Liza Richardson at KCRW floating poetry with music over airways. There was Suzanne Lummis, who captured this era in a book in an anthology entitled Grand Passion, highlighted in an article by L.Á. writer, Erin Aubry.

And that was just the Westside, things were popping all over L.Á. Fifth Street Dicks in Leimert, the YaYa Tea House in MidTown, Chinatown events and Olvera Street and even in Union Station where poets posted for Chiwan Choi and Writ Large Press for 90 days straight. We read in libraries, festivals or political rallies. Anything that reflected the city. I helped in festivals like When Worlds Collide in Long Beach and The World Beyond, merging Beyond Baroque and the World Stage and Mujeres de Maiz at Self Help Graphics in East L.Á. We went to South by Southwest in Austin, Texas or rocked our own House of Blues when Poet-girl Roni put us on stage with Pam Grier on Sunset.

But Michele T. Clinton’s class altered my pathway the most. Her workshop at Beyond Baroque felt like a tomb opening on Easter Sunday after millions of midnights in gloom. Her Women’s Writing Workshop opened me up and honed my craft. It gave me good examples, it held a bar and set the stage, it gave me a springboard so I could stand alone. Michele always greeted us with love, light and words, scenting her sessions with candles, leading meditations or telling jokes and I always left feeling cleansed. She blessed us with poets like Ai, Sharon Olds or Yusef Komunyakaa and her own friends like Sheshu Foster and Keith Antar Mason.

Our class produced many greats, people like Michelle Serros, Nancy Agabian and Maria Cabildo, Liz Gonzales and Nancy Padron. Serros, Agabian and Cabildo produced our own poetry troupe, “Guava Breasts.” The Guavas threw tampons with stanzas scrawled across each tube to punctuate poetic points. Tampons back then were so paper thin you could roll a joint with the thin outside wrapper.

Sometimes I think about the good stuff that’s gone. Places like Eso Won where I’d go and talk to James about the world and to see what others were doing on the page. I’d often buy books I couldn’t afford to help keep places like his in business.

Sometimes by just being out, you furthered your chances. I found fliers announcing publications all the time. Once I found a flier on a black Beyond Baroque shelf, announcing a new magazine called “Caffeine.” Caffeine put L.Á. poetry on the map. I was in their inaugural edition, with Charles Bukowski and Eloise Klein Healey and I’d often take a Caffeine magazine stack to Fifth Street Dicks or The Stage.

But I always returned to Beyond Baroque’s creaky steps. Once, after a reading, I sat near a Santa Claus looking guy. He snatched me aside, “You know I stole my wife from a convent. Read Letters to A Young Poet, by Rumi,” he said, “Then read all of Neruda’s ‘Love.’” I read Rumi and all of the Pablo Neruda I could find. I mean, who could resist a guy who snatched a girl away from God?

Anything was game. Poetry and performance mixed. Wanda Coleman read and barked like a dog. Bukowski threw beer bottles over folks heads. The Watts Prophets told America, “These Niggas Ain’t Playin,” which later became entry song for the movie “Judas and the Black Messiah.” Everything was happening at once. Akilah Oliver performed naked, Bowerbird tossed us instruments to shake and Bob Flanagan hammered his own johnson.

The last time I saw Bob, he was in a hospital bed at the Santa Monica Museum of Art, coughing and trying his best to look upbeat. But I could see he was sick. A poem he penned circled the museum wall like a halo and multiple people walked up to Bob’s bed, where he practiced performance art right up to the end.

But even in death, poetry saved us in so many ways. I did a show called, “I Didn’t Survive Slavery for This!” I did a reading when my own father passed, called “They’re dead, but we’re not.” I formed multiple allegiances and I made many life-long friends, forming other groups like “Cantaluz” featuring the unflappable Amy Uyematsu and the sage-whispering poet Nancy Padron and L.Á.’s own Gloria Alverez and Wendy James. We read each other’s rants, like Steve Abee riding the bus, or formed more troupes like V Kali’s “The Ovary Office,” taking our ovaries to the L.Á. Festival of Books and demanding reproductive rights.

We did everything. We were unafraid of being offensive or contrary and places like Beyond Baroque made us all feel safe. Whether it was Nancy Agabian crocheting a penis on stage or Michelle Serros’ race riot poem, “Chicharones.” A few years later, I became a BB Board Member and stayed eight years straight, passing the baton to Michael Datcher of the World Stage. Later, I taught my own Master’s workshop I titled “Write Like You’re Gonna Die,” and then hosted Beyond Baroque’s Wednesday night poetry workshop myself, seeing my poetic life come full circle.

Beyond Baroque will always feel like home. A boat. An anchor to keep from floating away. I busted my poetry cherry on its hard, onyx stage and published my first poems after finding a flier in their lobby. Poetry got me through the most beautiful and violent times in the city, the Rodney King beating, a riot that torched the sky, trying to be a mother while ducking a drive-by. Beyond Baroque saved me in the only way a person can be saved, in the heart, in the lungs or the way water marinates shore, like a baptism, or birth, or a bath after a long, hard shift, or a raft on a turbulent sea.