I used to think I was born out of place, out of time; as if the Earth spit me out.

Allow me to explain.

My parents were undocumented Mexican immigrants, moving to the United States in the early 90s to pursue the ever-elusive American Dream. My dad, Jose Rosalio Lopez, arrived from Guadalajara, Jalisco, in 1990, while my mom, Maria Elena Diaz, arrived from Compostela, Nayarit, in 1994. They met in the city of Bell shortly after my mother arrived, having moved into the same apartment complex that my dad lived in. He lived in one of the front rooms with his brother and father, my uncle and grandfather, while my mom moved into a room towards the back of the complex with her sister, my aunt. A year later my parents began to date, were married in January 1998, and I was born a year after. My sister Isabel was born two years later, in 2001. My parents received their permanent residencies sometime in 2018, finally dispelling the notion of their illegality and the fears of deportation that had always clouded my family.

Moreover, I was born at 12:30 PM on April 16, 1999, at Mission Hospital, formerly located in Huntington Park. I say “formerly located” because the hospital no longer exists. The site of the hospital, located on the corner of East Florence Avenue and Mission Place, is now occupied by a Smart & Final. Mission Hospital went bankrupt in April 2008, and was demolished later that year.1 Largely reliant on Medi-Cal and other government programs to cover patient-care costs, the closing of Mission and the termination of all its employees was a serious blow to Southeast L.Á. communities as Mission provided crucial healthcare services to thousands in one of L.Á.’s most densely-populated and underserved regions.2

Yet, it was a bit surreal discovering the medical institution I was born in no longer existed. Though I never returned to Mission Hospital in my youth, I went to nearby St. Matthias Catholic Church, where I had catechism and performed my First Communion, and I frequently visited my pediatrician who had her office in the Mission Medical Offices across the street. Living in close proximity, I realized just how underfunded and disregarded, almost invisible, the Latino community was to broader Los Ángeles County policy and funding. The removal of crucial services and resources in my high-density and underserved community transmits a feeling of precarity, disregard, and ambivalence that colors my community’s relationship to broader L.Á.

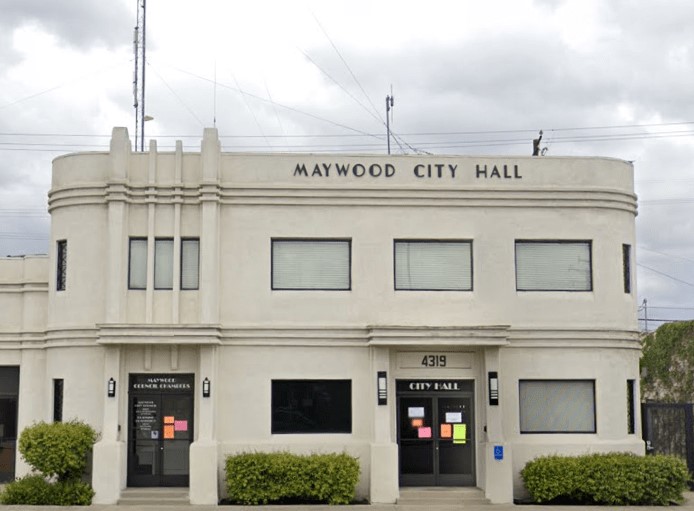

As a result, I felt immense alienation from my surrounding environment and Maywood, the Southeast L.Á. Gateway city I’ve lived in my whole life. With an area of 1.14 square miles3, Maywood is the third-smallest incorporated city in Los Ángeles County, located near the L.Á. River and the 710 Freeway and directly next to abandoned warehouses and industrial buildings alongside the border with Vernon. My environment is characterized by cold gray concrete, empty lots, littered trash, and toxic plumes exiting industrial chimneys.

Besides this, I had no deeper historical or cultural connection to the city; I felt a tension, a sort of incompatibility, between the culture my parents were imparting onto me and the environment I was born into. I felt neither Mexican (as I had never experienced life in Mexico) nor American (as the prevailing hegemonic group sees me as an intruder). This barren and destitute landscape produced an alienating atmosphere arising from my profound sense of detachment. I felt no connection to Maywood, even less so Southeast L.Á. This place felt very much lifeless.

Reading the second edition of Mike Sonksen’s Letters to My City has been a profoundly transformative experience. Letters to My City is a collection of essays and poetry that examines Los Ángeles, dubbed the “postmodern metropolis.” Mike Sonksen, a third-generation Los Ángeles native, combines two decades of research, field experience, and personal observations to bring the vibrant history of many of L.Á.’s unknown regions to light. Sonksen more closely examines L.Á.’s literary and musical culture, contemporary community organizers and activists, and Sonksen’s own family history and life. The majority of the history recounted in the book comes from first-hand narratives and interviews told directly to Sonksen. The second edition comes with a new essay on the late Mike Davis (legendary author of City of Quartz and longtime mentor & intimate friend of Sonksen), a new essay on the local history of Time and Space, and a teaching guide to help educators incorporate the book into their curriculum.

Mike Davis is a crucial figure in Sonksen’s development as a person and scholar. “Writing Is a Verb: Mike Davis and Social Consciousness” is the essay that opens the book, and it is a remembrance essay about Mike Davis, renowned historian and urban theorist. Sonksen became Davis’ student while Sonksen completed his undergraduate degree at UCLA. In the essay, Sonksen reviews the major insights of Davis’ historical work and further describes his profound personal impact as an educator. Davis’ notions of Los Ángeles being the postmodern metropolis are expanded upon by Sonksen. By postmodern metropolis, Sonksen and Davis mean that L.Á. is a uniquely diverse multiethnic city with an expansive and evolving urban environment imbued with rich cultural and historical bubbles that have had profound impacts on American culture. Reviewing Davis’ book Ecology of Fear, Sonksen writes:

Loaded with facts and anecdotes, he meticulously recounts the history of frequent fires in Malibu and across the chaparral foothills in comparable sites like Laguna Beach…One thing many of his critics do not understand is that he is not prophesying doom; he wants us to see how many [of the] lives [lost] and destructive consequences could have been avoided if more informed policy decisions were made. In the case of Malibu, how many lives and hundreds of burned out houses could have been saved if officials would have listened to Olmsted Jr., the nation’s foremost landscape architect and designer of California’s state park system [who advocated public ownership of some 10,000 acres of Malibu property before it was opened to development] 90 years ago?

Lastly, Sonksen explains Davis’ profound impact as an educator and mentor: “Beyond the constellation of ideas he introduced me to, he taught me how to be a more complete human. I learned about social consciousness from how he encouraged students, shared books, and emphasized the importance of real-world experience.”

In a later essay on Marguerite Navarrete, Sonksen’s profoundly influential 3rd and 4th grade teacher, he explains he aims to emulate the kind of instructor she was. I believe this sentiment holds equally true towards Davis. I believe Sonksen has embodied and imparted that same spirit of encouragement and support he felt from his own teachers.

“A Local History of Time and Space,” the second new essay is part manifesto, part memoir: Sonksen explains how learning one’s local history and geography can give one a sense of identity and community, leading to becoming an engaged citizen and activist. The purpose of sharing his story is to highlight the insight of local history and geography. Sonksen explains:

Ultimately students’ interest in their own locality makes a great segue toward civic engagement, service learning, personal values, and even identity and belonging. These same results transfer to anyone that makes the time to engage local history no matter their age. To learn local history is empowering and helps one become more of an engaged citizen of wherever they are. In some cases, it can even connect folks to their ancestors and forgotten family stories.

I can say that Sonksen has succeeded in imparting this lesson about local history, as my perception has definitely changed after I began learning the history of my city and surrounding subregions. In order to fully assimilate this lesson, I decided to document my family’s and my own personal history at the beginning of this essay.

The postmodern metropolis is composed of millions of lives that have undergone uniquely significant yet unheard experiences, but it is our duty as engaged citizens and empathetic people to record these family histories and to share them. Doing so honors ancestors and empowers the individuals and communities with an unshakable sense of belonging, adding one more voice of joy and resistance to the tapestry of love that makes up a city. The Maywood that I regarded as cold, barren, and lifeless has blossomed, gaining a new vibrancy. The book has given me a new framework with which to understand my immediate community and the surrounding areas. The essays on South Central, Florence-Firestone, and Boyle Heights resonated deeply as these are communities near me and ones that I frequent. I better understand the people currently fighting to uplift our communities against environmental racism through organizing and creating art. Furthermore, I now understand the significant events that impacted the development of these regions, such as the 1965 Watts Uprisings or the 1992 Los Ángeles Uprisings. The latter holds significant weight for Sonksen, as they occurred right before he graduated high school and began his undergraduate studies at UCLA. His studies there with professor Mike Davis would then give Sonksen insight into the history and class relations underlying the development of Los Ángeles.

Letters to My City is an indispensable resource; it’s a reference for the history of this place and the people that have lived here. It is also a memoir, with Sonksen sharing intimate details about his life. Poetry is the main form, alongside essay, that Sonksen decides to relate LÁ’s history. Rich in alliteration, musicality, and myriad cultural references, Sonksen’s rapid-fire verse captures the heightened pace of urban life in LÁ through the musical styles of one of its major cultural contributions: hip-hop. Sonksen’s poems have a recognizable musical element that makes reading them a fun and rewarding experience. While this collection deepens a person’s knowledge of Los Ángeles history, more importantly it profoundly shifts their understanding and relationship to Local Time and Space.

Sources

1. Deborah Criwe, “State Budget Crisis Hits Huntington Park Hospital,” Los Angeles Business Journal, October 26, 2008, https://www.labusinessjournal.com/healthcare/state-budget-crisis-hits-huntingon-park-hospital/.

2. Sam Savage, “Community & Mission Hospital of Huntington Park Shutting down Mission Campus, Terminating Workers,” Redorbit, March 5, 2008, http://www.redorbit.com/news/health/1283024/community-mission_hospital_of_huntington_park_shutting_down_mission.

3. “City History,” City History | Maywood, CA, accessed July 19, 2023, http://www.cityofmaywood.com/266/City-History.