Family. Immigrants. Immigration. Los Ángeles. These are the themes that are woven throughout Xochitl-Julisa Bermejo’s debut poetry collection Posada: Offerings of Witness and Refuge (Sundress Publications, 2016). Over the years these themes have stayed with her, expanding, giving her a clearer sense of who she and her family are. Having grown up on the Eastside of Los Ángeles and in the San Gabriel Valley, she spent much time with her large extended family haciendo traviesos with cousins around her grandparents’ Boyle Heights home. However, Bermejo’s story begins with the arrival of her paternal grandparents and their three children (her father the oldest) to Los Ángeles, to “the little house on Fairmont Avenue,” from Teocaltiche, Mexico as Bremejo retells in the collection’s opening poem “The Story of the Stolen Metate.”

In “…the Stolen Metate,” Bermejo sets out the caveats for what is to follow: the weight of memory—“Maybe remembering hurts dusty shoulders”—what has to be given up to survive, and the weight of the decision to immigrate and what it means. “My father found his original green card and gifted it to me.” What her father had to sacrifice, and by extension his parents, that enabled her to be born, to attend college and even be able to contemplate being a writer, much less becoming one, is wrapped up in that ID. And holding that green card, it’s like branding a cow. This is who he is, a Mexican immigrant. This is how American society views him and people like him.

Posada is also a piece of Los Ángeles literature. It’s a collection about a family living on the city’s vibrant Eastside. It’s about a girl and woman named Xochitl. It’s about Chicanx Los Ángeles and its history.

From the cover photo of the front steps to her grandparents’ house in Boyle Heights, to the poem “Solano Says Goodbye,” where “I moved to Solano Canyon to feel close to history/to coax Chavez Ravine ghosts from darkness,” to the poem “Search and Recovery” that reminds readers of the perilous journey that people, who look just like her, take across the Sonoran Desert to have a better life, Bermejo tells a uniquely L.Á. story, while at the same time being universal.

As a debut poet, she is able to tell such a story from a place of knowledge and deep understanding, with the confidence, necessity and care of a veteran poet. Her word choices capture the necessary importance of home and finding home. How one or the other or both linger within a person. This is present in the poem “Hills of East L.A. Are Home” where “The hills rise over the houses and traffic of the city/like memories gently rising from my aunt’s mind/ […] she doesn’t live in L.A. anymore, but the city/doesn’t leave her.” Bermejo’s aunt tells a fragment of a family memory to her niece, the poet and story teller, as Bermejo sits “on my bed in Solano Canyon.”

It is here in Solano Canyon where Bermejo feels close to the molding of her family’s and Los Ángeles’ history. With her Chavez Ravine poems, inspired by Don Normark’s photos of the now demolished Mexican neighborhoods, long replaced by Dodger Stadium, Bermejo is re-membering and contextualizing. With lyricism she creates snapshots of these people and neighborhoods with carefully chosen images like the “stone-black eye” of a young girl keeping lookout with her stuffed bunny in the poem “Mud-Caked.” Here it’s “her bunny” keeping watch with her from “her patch of dirt.” Bermejo understands the necessity of letting these few words carry the historical weight of the poem, of Angeleños displaced from their homes reverberating from past to present, like her own family. It creates a deeper understanding of people and place and their connection to place. Of Los Ángeles.

In poems of her family living in Boyle Heights and her Chavez Ravine poems, Bermejo brings this true Chicanx L.Á.—away from the overused tropes of a lack of history, of being without, of L.Á. is Hollywood—to the fore. She paints this Los Ángeles through her personal experience of living in L.Á. that, as the years go by, is being brought to life more frequently in Los Ángeles literature by the likes of Stephen D. Gutierrez, Nikolai Garcia, Vickie Vertiz, in Daniel Oliva’s anthology Latinos in Lotus Land and Tía Chucha press’s Coiled Serpent: Poets Arising from the Cultural Quakes and Shifts of Los Angeles.

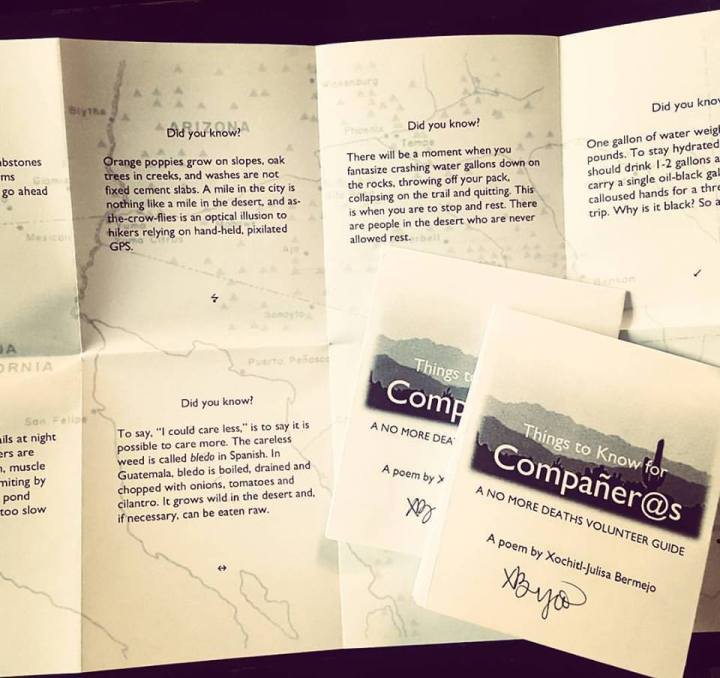

In the second half of Posada Bermejo creates a poetic volunteer guide for desert aid workers helping migrants who crossed the border and has penned poems that flesh out the voices and portraits of migrants. This stems from her volunteer experience with the direct humanitarian organization No More Deaths. In these poems Bermejo dives past the political rhetoric to capture these immigrants as human. She has heard and witnessed these stories.

Did You Know? One gallon of water weighs 8.35 pounds […] Migrants carry a single oil-black gallon in calloused hands for a three or more day drip.

Her words force the reader to contemplate the consequences of this reality. And in the poem “Face Wipes for Sensitive Skin” she gives added weight to humanizing moments of realization, allowing them to resonate and linger over these immigrants by giving them their own stanzas. “Did you hear the couple say whichever one makes it/will send for their daughter?” and “How can this be/my country?” These realizations are voiced by Daisy, a volunteer Bermejo works with in the poem; a volunteer that can stand in for any regular American or White America.

Yet, though each poem speaks to Bermejo’s talent as poet, and she beautifully manages to weave the themes of family, immigrants, immigration and Los Ángeles together throughout, there are several poems, mostly to a minor degree, that do not quite fit into the larger narrative or fit in the order she has organized her collection. For example, “The Art of Touch” and “La Perrera of Chavez Ravine” most noticeably shift the collection to the theme of romantic love that is absent from the rest of the collection. “He touched my naked body […]” “The Art of Touch” begins. “At night, she entwined his taught body to her,” is one line in “La Perrera of Chavez Ravine.” Still, these two poems are the only ones that interrupt the through lines of the themes in any significant way.

In the end, Bermejo wants to get these stories of family, of place and of immigrants right. She does so by giving them the space to be told holistically, not only from her experience and her interpreter’s voice, but from their voices as well.

Bermejo’s work celebrates Chicano identity and history. Great review!

LikeLike