What is a song’s function? How might an empress on the mic be a rhythmic healer in a nation that is grieving? In an America where so many have lost their inner song, and in some cases, their lives, to colonization, the Divine Feminine—the one who sings, holds space, arouses spirit—she carries soul messages. If we have the courage to listen, we hear America craving to heal, yearning to celebrate our light, while honoring the shadows of suffering. The singer inspires us to discover, conjures the flesh of life and loss that is humanity’s dance.

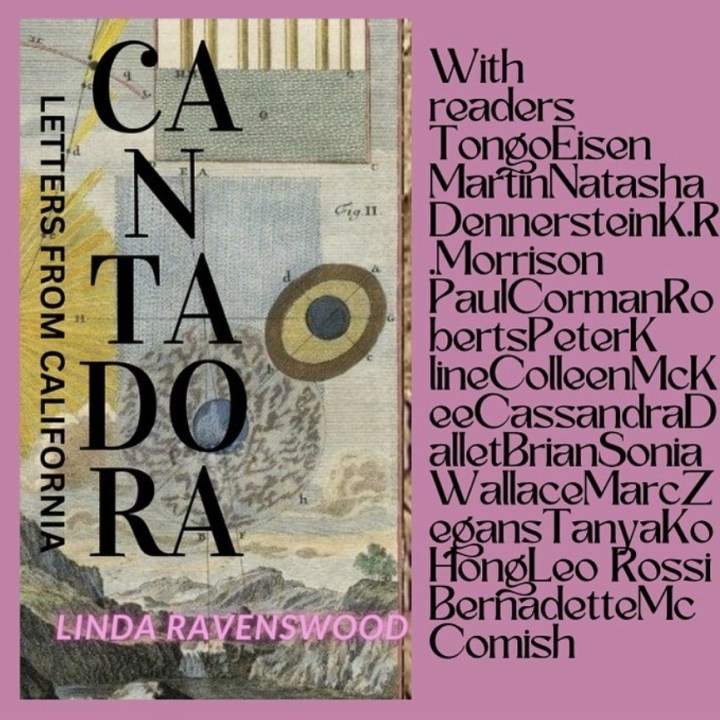

In Cantadora – Letters From California, Linda Ravenswood unravels her personal country through an occupied and often cruel nation, offering fresh windows into mixed heritage, migration, otherness, and gender relations. A creative daughter of Los Ángeles, Ravenswood’s testimony offers reliable access to such complex human contexts, L.Á.’s history ripe with ethnic, economic, and cultural diversity. Cantadora’s multi-cultural focus extends beyond temporal contexts of “country,” into varieties of poetic style and form on the page, encouraging readers to expand beyond barriers of poetic tradition. Her portals of free verse siren readers to discover what is both powerful and precious about what it means to both belong and to feel estranged.

Ravenswood organizes Cantadora into seasons, as readers submerge in an extended metaphor regarding cycles of self-discovery. Love country. Cultural country. Immigrant country. The country of human hearts enduring borders within borders. The country we travel when born into more than one ethnicity—all quintessential portals into oneself, of the people writing from diverse landscapes like Los Ángeles. Adding to a myriad of personal memoir, Ravenswood threads through empath country—singing for ghosts of the West she cannot unhear. Readers begin in spring, in the breath of mother, in the struggling blossoms of belonging and in the budding of the in-between. Ravenswood submerges us into a memory, into her search for self when what’s feminine wants to shout in cultural environments that tell little girls to behave, of a budding ostara within every child told to be seen and not heard. Cantadora’s spring section looks a lot like a garden—a wildflowering of manifold, rule-breaking free verse that tells of American otherness, a young poeta eager to enlist her gumption. From “Springtime 1”:

When I was a child I fervently worshipped the tiger inside my mouth; parted lips, geographic tongue, all Indus Valley – til mother thrashed me in green grass & smashed me in the cradle, screaming Wake up brown girl, it’s spring.

In Cantadora’s summer section titled, “The Nautilus Within,” readers discover what might be the most beautiful genealogy of poets and their craft, “Poetry is a Shapeshifter.” In this poem Ravenswood echoes Marge Piercy and Pablo Neruda through syllabic rhythms, alluring diction, and accessible imagery. The effect unmasks a poet’s responsibility as “somewhere between student & teacher/shaman & servant, magician & fool,” among other gorgeous stanzas celebrating poets. At the same time, Ravenswood exposes the dirt beneath a poet’s fingernails. Intentionally wedged between “this message has no body” and a grandmother tribute titled, “The Saint of Memory,” Ravenswood’s song for poets invites readers into a whirlwind of duty and gift that is the life of a wordsmith. Braided in Ravenswood’s other poems about mixed heritage, life as an L.Á. teen, and poems about an empathic mother born a precocious daughter, “Poetry is a Shapeshifter” shows us a Ravenswood in reverence to her craft—the mind, body, and soul trinity that constitutes La Cantadora.

In the spirit of divine numbers such as three and trinity concepts, readers find a poem placed in the center of Cantadora, “We did this on earth – Triptych,” an archeology of human country in a life—death—rebirth format. Ravenswood’s poem appears on the page the way a triptych would on an altar, an offering of both grand yet also, simple acts within a lifetime, legacy and echo, both big and small.

Additionally placed in the summer section of Cantadora and in a true Ravenswood twist of color is “The difference between the pool guy/ & the gardener/ & why you want to f&%k one/ & not so much the other/ & it’s racism.” Here Ravenswood shapeshifs in her writing style about the gravity of stereotypes and discrimination’s inconsistencies through dry sarcasm landscaped by domestic and sunny motifs. The outcome is breath after heavy, more thematically spiritual poems, a lighter mood following the intensity of legacy and human impact poems. What’s interesting, however, is her commitment to uncovering critical social wounds doesn’t disappear; instead, Ravenswood approaches what’s also impactful differently than she does in neighboring poems. What’s in dire need of a critique of power meets crass humor wrapped in summertime imagery, and a racist patriarchy receives quite the sunburn. Ravenswood draws readers into ordinary life settings that are both amusing but sobering, regarding inequity. Where there is the damage that comes with double standards and self-deception, there is humor and suburban household frameworks to walk us through it.

Los Ángeles and the West weave throughout Ravenswood’s collection, but the “Red Car to Infinity” transports us to autumn, the season where old things die away. Waiting for readers is a nostalgic highway ride to the ghost of an old Southland long dead, an homage to growing up in a place where listening to radio stations “felt like a secret held between us.” The effect is appreciation for a synesthetic L.Á. that aroused our senses, rather than LA’s gentrified drift to wealth, reality TV, and cell phone screens. The effect is an understanding of Ravenswood’s dimensional range as a poet, as such an intimate and exciting, former version of Los Ángeles was her amusement park and obstacle course toward self-discovery. In Cantadora’s season that honors inevitable demise, Los Ángeles becomes a key character to understanding loss, a kind of protagonist and antagonist fused into one setting that recruits a young Ravenswood into becoming a creative risk taker—a poet who allows traditional formats to erode, as she rebels in her line structures, diction, and punctuation.

Winter’s section, “The Long Trip Home” returns us full circle, to the beginning of seasonal cycles by uncovering the cold shadow of humanity, and most heart-wrenching is a tribute to “7 children who perished in ICE detention.” Appropriately placed in the dark nights of Cantadora, this poem empathically salvages the legacy, life, and innocence of the children in a kind of incantation of the four elements, a healing cry and call for protection. Readers step into an ethereal fluidity of time—where country becomes spirit, earth, air, water, and fire—nesting souls of wrongfully lost and discarded immigrants. Ravenswood’s winter section calls readers to hold space for various contexts of grief; in the same way songs enlist space for rhythm and measure.

Ravenswood’s carefully enlisted humor in Cantadora functions as a kind of healer, balancing out heavy expositions of human struggle. Readers dance from soul ache into a chuckle, a freestyle into life cycles of the human journey in the context of some severe American realities, both within memoir and beyond the author’s own personal experience. Ravenswood recounts critical historical moments such as Irish migration in her poem, “The DNA to preserve proved contrary to capital gains,” while poems about Spanish colonization or the scars of the Holocaust hieroglyph within and around more immediate personal accounts of her family history. What she beautifully executes, as a result, is the hereditary overlap of social and cultural anatomy that soundtracks her self-discovery, alongside personal family terrain that shapes her. Readers conclude with a “Bus lady” going nowhere, though who this woman is, at least in this review, will remain a discovery awaiting Cantadora readers.

Cantadora’s empowering integration of personal, social, and cultural ingredients speaks to Ravenswood’s prosperity to enlist dichotomous human conditions as doorways into self-discovery and acceptance, as is the case in her poem, “Towards California.” Leaving herself and submerging into a man on a train, readers are invited to put on their empath hats, submerge into a Mexican man’s American experience, climb into his humanity, feel his love, his concerns, his day-to-day life that’s normally masked as “immigrant.” The poem ends in a stanza that paradoxically highlights his similarity to everyone else within his mystery and his difference: “/maybe he is alone/like everyone else/.” In this way, Ravenswood enlists diversity to bring us together, into belonging, without silencing the glory of our differences.

Throughout her collection, Ravenswood makes it very clear—songs carry everything—the beautiful and the rhythmically treacherous, stolen land and lost spirits, ghosts and wild animals hibernating in our mouths, hungry for us to sing their names. Songs carry the elements, rivers and west coast valleys and deserts, Molotov cocktails that bleed from our veins like a whole other set of ancestors, a whole other country without the borders of an America to which we are bound. Songs carry both a nest and a spaceship for anyone who exists as not one or the other, anyone who holds revolutionary potential. Linda Ravenswood welcomes us to come along, but pack a warrior bag and some steel-toe boots—Cantadora serenades us into our inner seasons, our own “nautilus within.”