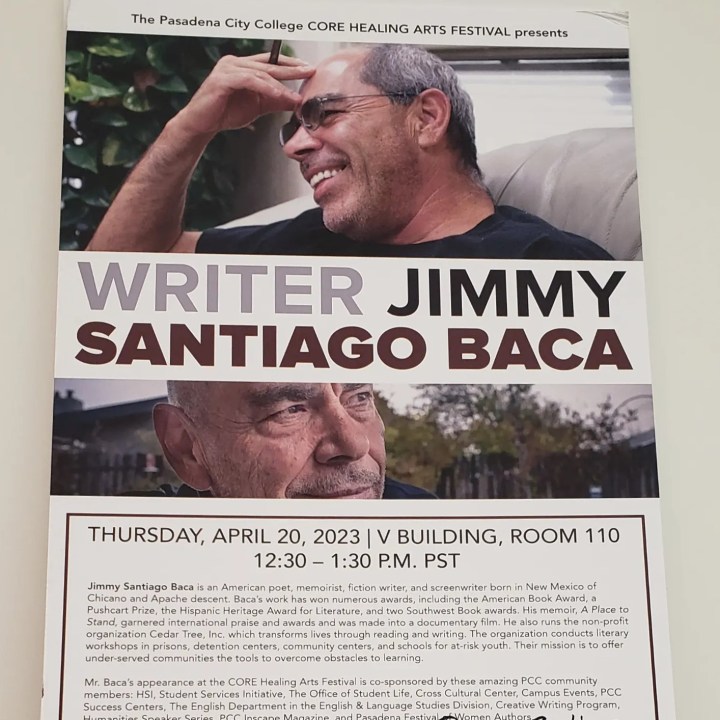

The room was packed. All but one seat was taken. Poet Jimmy Santiago Baca stood in front of the projector screen, mic in hand. He was telling his life story. A story about being abandoned by his parents, running away from the orphanage his grandmother placed him in at 13, the five years he spent in jail on drug charges where he learned to read and began to write poetry. Where he came from nothing, in New Mexico, where at one point all he had to give was a single poem. And how, since then, through hard work and passion, he’s built the life and literary career he’s wanted.

He spoke, peppering his language with fucks and shit, as if he was telling friends a story in a bar. Standing near the door acting as door monitor was PCC English Professor and Poet Emily Fernandez.

It was the 20th of April. I was on the campus of Pasadena City College (PCC) for their Healing Arts Festival, sponsored in part by PCC’s literary magazine INSCAPE.

As Baca’s reading and talk continued, students continued to arrive.

PCC’s Healing Arts Festival is part of their CORE (Community Overcoming Recidivism through Education) Scholars program aimed at serving and supporting incarcerated, formerly, and system-impact students in their reentry into their communities by empowering them holistically so they can succeed in their education and beyond, according to the program’s website. These were students who could relate to Baca’s story.

As Baca spoke, he made sure to emphasize that he made some big mistakes. Mistakes that landed him in jail, mistakes he made in jail—broke up a prison fight, inmates assuming he was crazy, that something must be wrong with him for breaking up a fight—through honesty he called “all my bullshit.”

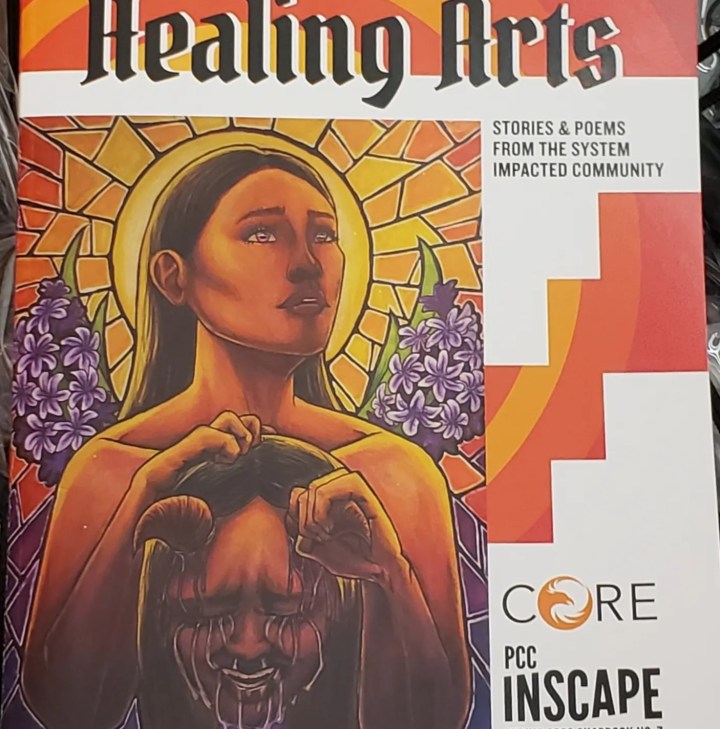

The students in the CORE Scholars program published a chapbook of their work. They told their stories so nobody else does. To ensure they’re told honestly and accurately. That was a point Baca made sure to emphasize, especially during this talk to the CORE students after lunch. Being both half Chicano and Apache with a criminal record, he understood all too well the racist assumptions and stereotypes American society forces on people with backgrounds and circumstances like his and the CORE students, that convince them that they are less than, beyond help and love and that of empathy. Beyond rehabilitation.

Baca told the students: stop letting white people tell you who you are.

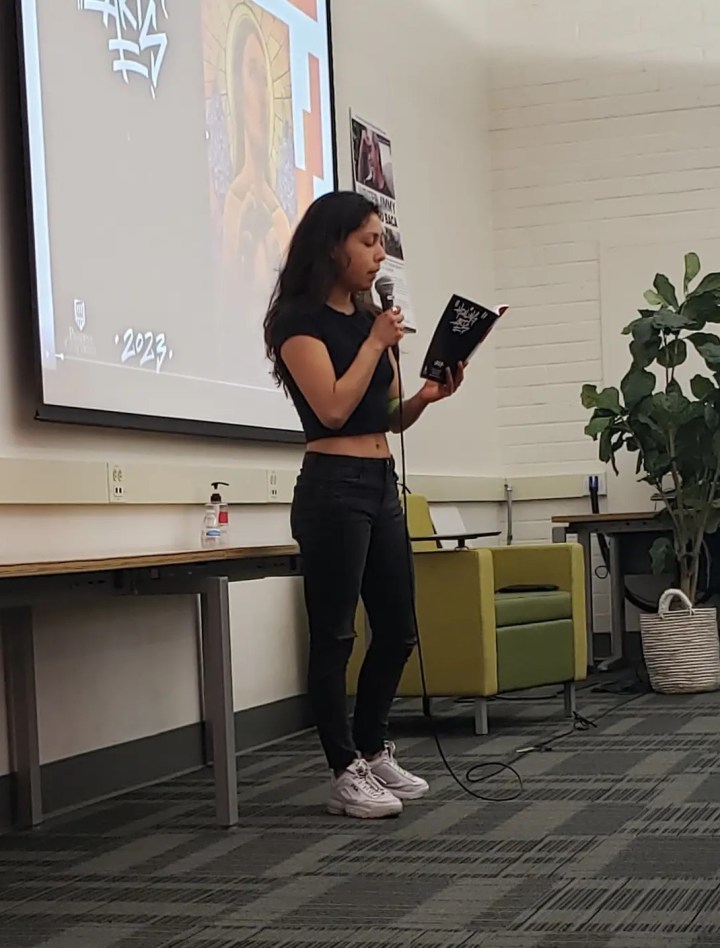

By writing, telling their stories, the CORE students learn who they are. They can use writing as one part of therapy. This became evident when students shared their words during the short open mic. The poems spoke to their mistakes, which some said landed them in jail and how they wanted the chance to learn and grow from them. Some powerful lines they read included: “Started lonely, naked, powerless…” and “Will your devotion waver…”

One student wrote an ode to the CORE program, how Dr. Ogden helped build his confidence to see himself as a person who could achieve an education, reach goals that society had beaten into him, weren’t his to achieve. Goals that students like Larry Valez and Monica Gonzalez were obtaining, through holistic learning. Through a program funded by the California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office. One of 44 campuses “allocated $113,636,” to “grow [and/or] establish on-campus community college programs for formerly incarcerated and system impact students,” CORE’s website explains. Plus, since then, the Chancellor’s Office has awarded CORE an additional $178,000.

I could tell a supportive community had been built by these students as well, exemplified this day by students cheering each other on when they read in front of the class.

Also, in the afternoon, the students heard a success story from a former CORE student and local poet Adrian Ernesto Cepeda. He spoke to the students as an inspiring CORE graduate. He spoke on his sobriety—10 years—and how his life changed when he took a class at PCC from Dr. Ogden. How she challenged him.

Cepeda read several poems, one about a Juan Felipe Herrera reading he attended and noticed how similar they are in what they write about and how they write about it—who they are—connecting on a cultural level.

To cap the day, Baca returned for a healing arts circle where he provided time for students to write on a prompt he gave them. About writing on the darkness they have inside them, the dark space. What is it for each of them? And how they can find the light or have already.

Then Baca allowed students to share what they wrote as he listened intently. Praising students, like himself, who’d fought hard, and are still fighting hard, to see themselves as completely human.

It was great seeing you there!

LikeLike