By Brian Dunlap

Sunday was the first time I attended Slow Lightning Lit’s open mic at The Book Jewel in Westchester. The open mic, hosted by poet Peggy Dobreer, began online as a place for people to hold space for each other and connect by sharing their voice during the Pandemic.

Featuring this month were two Orange County Poets I respect, Gustavo Hernandez and Ellen Webre. Moontide pressmates of Dobreer.

The open mic was sparsely attended, but everyone who showed, more than appreciated the community taking place. An unexpected surprise was when poet Derek D. Brown arrived right before the open mic began. Instantly, Dobreer broke out into an excited greeting of familiarity and warmth, like an old friend who hadn’t seen Brown in a while. A friend I hadn’t seen in a while either.

Slow Lightning Lit also conducts a Monday-Friday online meditation/writing series where people from around the world connect with each other by spending the first 10 minutes meditating before working on an integrated writing prompt. Stemming from these guided meditation and writing sessions, Dobreer independently published the poetry collection Slow Lightning: Impractical Poetry, featuring poets such as Lisbeth Coiman, Diane Sherry Case, Alicia Elkort, Brendan Constantine and writer Janet Fitch.

However, when the open mic began, Webre and Hernandez read first.

Webre, who co-hosts the open mic Two Idiots Peddling Poetry, in the city of Orange, read from her debut collection A Burning Lake of Paper Suns. It’s a collection of love poems, that are, as the jacket copy states, “scintillating through a heart bursting at its seams. With the decadence of stars and pomegranates, Ellen Webre’s poems illustrate the transfiguration of a girl to a monstress. Here she is ravenous, and tender for what desire haunts.” It’s the images she creates that make her poems truly her own.

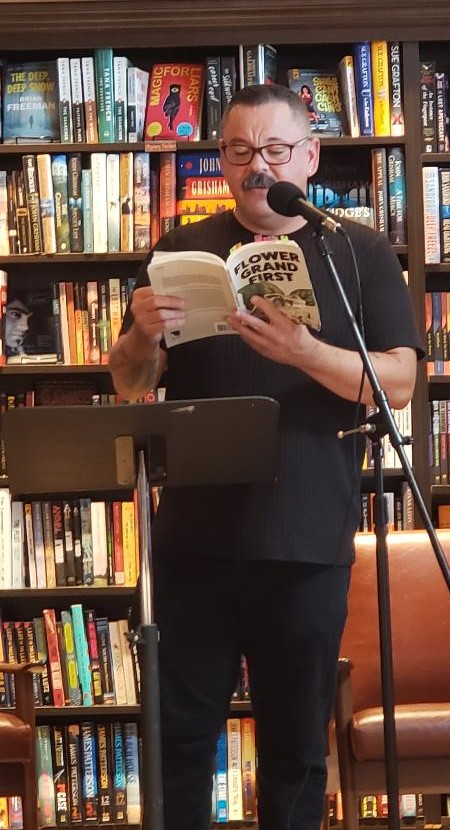

Hernandez read from his debut collection Flower Grand First, as well. It’s a collection about place, specifically Hernandez’s hometown of Santa Ana. Primarily through the use of Santa Ana, and other places such as Jalisco and San Isidro, Mexico, Hernandez “moves through the complex roads of immigration, sexuality, and loss…honoring family and recording a personal history,” as the jacket copy states. When Hernandez read “Noviembre,” having recently lost my grandmother, my mother’s mom, I knew my mother, sitting next to me, would feel it deep in her bones. “My mother would not visit her mother’s grave this year. She would help her family adjust/to Mission Viejo for eight days, Santa Ana and beyond for the rest of her life.” The memory of a mother’s sacrifice for her family.

After the features, mostly white poets read. It was great to hear such distinct voices grace the mic, reading lighter fare than I usually hear at the BIPOC-centered open mics I often attend. A nice break from the heavy topics—race, place, history and the intersection of the three—I always engage in.

After I read my heavy abortion poem “I Don’t Want To Live In 50 Sperate Nations,” defending the importance for a woman’s right to choose, Dobreer said half serious and half joking, that I should run for Senate. There needs to be more men in the Senate that thought like me. I only smiled humbly in response.

It was especially nice to hear Derek Brown read, who performed one hell of an empoweringly sexy love poem about the ideal woman who is strong, complex, complicated and intelligent and how he’d treat her in a way that respects those aspects of who she truly is, which aids in creating a truly loving and lasting relationship. Afterwards, my mother told me my dad kept nudging her during the poem as if to say, “Derek took the words I feel about you, right out of my mouth.”

Peggy Dobreer closed out the afternoon by reading two poems of her own

After the open mic, being so moved by Gustavo Hernandez’s poems about his parents, my mother knew she had to buy his book and had to thank him. As she thanked him for poems about his parents, how touching they were, especially when he read about his mother, my mother having recently lost her own, unexpectedly tears spilled from her eyes. Hernandez couldn’t have been more appreciative for how deeply his poems had touched her, how they were able to create such an honest connection with the audience. My mother couldn’t have been more appreciative for the words of comfort he gave her, from his own experience of losing his parents, that she could take with her.

For me, it was great to connect with Hernandez again, since it had been months since I had seen him last.

With a warm, heavy heart, my parents and I were tankful we had attended Slow Lightning Lit’s monthly open mic.