By Dana Isokawa

FROM: Poets & Writers

For our fifteenth annual look at debut poetry, we chose ten poets whose first books struck us with their formal imagination, distinctive language, and deep attention to the world. The books, all published in 2019, inhabit a range of poetic modes. There is Keith S. Wilson’s reimagining of traditional forms in Fieldnotes on Ordinary Love, and Maya Phillips’s modern epic, Erou. There is Maya C. Popa’s lyric investigations in American Faith, Marwa Helal’s subversive documentary poems in Invasive species, and Yanyi’s series of prose poems in The Year of Blue Water. The ten collections clarify and play with all kinds of language—the language of the news, of love, of politics, of philosophy, of family, of place—and, as Popa says, they “slow and suspend the moment, allowing a more nuanced examination of what otherwise flows through us quickly.”

For our fifteenth annual look at debut poetry, we chose ten poets whose first books struck us with their formal imagination, distinctive language, and deep attention to the world. The books, all published in 2019, inhabit a range of poetic modes. There is Keith S. Wilson’s reimagining of traditional forms in Fieldnotes on Ordinary Love, and Maya Phillips’s modern epic, Erou. There is Maya C. Popa’s lyric investigations in American Faith, Marwa Helal’s subversive documentary poems in Invasive species, and Yanyi’s series of prose poems in The Year of Blue Water. The ten collections clarify and play with all kinds of language—the language of the news, of love, of politics, of philosophy, of family, of place—and, as Popa says, they “slow and suspend the moment, allowing a more nuanced examination of what otherwise flows through us quickly.”

While the books share a sense of urgency and timeliness, in fact these collections got their starts years, even decades ago. So we asked each of the poets to share the stories behind their debuts—what experiences or scraps of language incited the book’s first poems and what insight pulled them through the process of writing and publishing a collection.

Many of the poets described accepting the time it takes for poems to arrive and learning that making poetry doesn’t always entail sitting at the desk, pen in hand. “If I am looking at the world through poetic lenses and thinking of all of my work through the lens poetry has gifted me, then the poems are being written and will touch the page when it is time,” says Camonghne Felix. Sara Borjas reminds herself that everyday activities like reading and cooking are also “a making.”

Several of the poets also said their books began when they wrote through their original subject to its opposite or counter. In writing about Blackness, Felix wrote about survival but also thriving. Heidi Andrea Restrepo Rhodes took on the ghost as “both the obstinate echo, as well as a willful, living fury calling us into question.” Jake Skeets wrote about the fields of Gallup, New Mexico, as a site of both desire and violence; Patty Crane found inspiration in beauty, but also the suffering and injustice that brings it into relief.

And all the poets credit the people who helped them along the way—friends who pored over drafts, editors who challenged them to be better, mentors who encouraged and advised, family members who offered support. All the people who remind us that behind every book is a poet, and behind every poet is a community—or as Crane says, “the threads that bind us to one another and to the world.” So we hope that when we lift up these poets and their collections, it is also a testament to the communities that stand behind them as artists and nurture them far beyond the pages of a book…

Sara Borjas

Sara Borjas

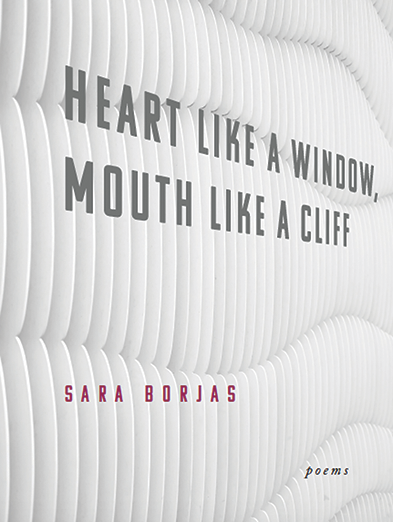

Heart Like a Window, Mouth Like a Cliff

Noemi Press

I am the scrape of the lowrider as it exits the driveway,

bothering the neighbors.

—from “Ars Poetica”

How it began: In my heart I wanted to love better. We are a colonized people putting ourselves together for hundreds of years. Much of our lives, ideas, values, and traditions are survival tactics. I wanted to see my parents as individuals but also through this lens and love them wholly. I didn’t want my heartbreak, or theirs, to be for nothing. So in each poem I asked: How am I making myself and my family more simple and responsible for our lives than we actually are? And I never really stopped answering, even through all the revisions and drafts, and even now. Many of these poems are me puzzling together how I show love and what and who I think deserves it and why. When I began working with Noemi, one of the first things my editor, Carmen Giménez Smith, told me was that I had a manuscript but not a book yet. This stands out as the beginning for me. This is when I felt for real compelled, capable, and honestly challenged to write this very specific collection.

Inspiration: Oldiez. Fresno. The reliability of crop rows and how you can see all the way to the end no matter what. Books like Whereas by Layli Long Soldier, Crush by Richard Siken, Blood by Shane McCrae, and MyOther Tongue by Rosa Alcalá; Anne Sexton; Rumi; “punk poetics,” as Juan Felipe Herrera says; the word no out of any woman of color’s mouth; Lifetime movies; Real Housewives; really, any drama where the protagonists are women; oranges from my dad’s tree and zucchinis from his garden; my mom’s sense of humor; all shit-talkers everywhere; my sister’s ruthless sentimentality and her writing—she’s an amazing writer but stays low-key; and watching and helping my friends work on their books at the same time.

Influences: Roque Dalton for his sentimentality coupled with self-ridicule and the tendency to exaggerate, Richard Siken for his associative genius and how he writes about love, Dulce María Loynaz for showing me that my parts equal a center and are not scraps, and No Doubt for showing how to make fun of the patriarchy. All these artists showed me how to be extra and be beautiful in it.

Writer’s block remedy: When I reach an impasse, I accept myself and treat it as a liberty. I don’t feel the need to keep going if I’m not excited about writing. I think that’s always bothered me about the possibility of becoming a writer, that I’m expected to produce writing. It feels very capitalist and very colonial to make any part of myself or my behavior a commodity. I try to break the habit by being okay with not writing. I watch TV and films, talk to my friends and family, read, watch shows about outer space, and go down rabbit holes looking up phenomena. I cook. And all that, to me, is a making.

Advice: Write toward honesty, then, really write toward honesty. Stop lying. As Bruce Lee said: “It is easy for me to put on a show and be cocky…. I can show you some really fancy movement. But to express oneself honestly, not lying to oneself—that my friend, is very hard to do.”

Finding time to write: Right now I have a dream schedule that creates an alternative problem of when not to write. However, I am not someone who can sit down and write like it is a job, which I am cool with. So I find time by reading and getting pumped about what others are thinking, asking, and their work leads me to writing. I’m an impulsive, and honestly, kind of dramatic, person, and my writing habits are equally volatile. If I’m feeling, it’s always deeply. If I’m writing, it’s always obsessively. I know this will probably be the only time in my life when I have this time, and I feel a pressure that accompanies that privilege, but I also feel really free.

Putting the book together: I cannot stress how crucial editors are. Editors make the poetry world go ’round. For a few years, I maneuvered papers around my bedroom floor, as poets do. But when I became strategic, it was because my editors challenged me. The poet Ángel García charged me to organize the book according to theme and that’s how I found imbalances in the narrative. My friend Julia Bouwsma, who was a hero in helping me make this book, said, “You can have a narrative without a narrative structure.” Her comment freed me. Carmen Giménez Smith did not let me get away with shit. One day she called me and said, “You wrote ‘heart’ seventeen times in this book,” and hung up. I needed to be checked, and she was really good at holding me accountable. Blas Falconer, in the kindest way, showed me where I was circling the wound, peeking all around it rather than through it. J. Michael Martinez pushed me to think about form, marginalia, the reader’s way of participating, and the kind of double consciousness that was at work in my speaker’s voice. Ultimately, I wrote new work, and mostly rewrote, sometimes entirely, whole poems. I consolidated poems. I wrote an essay called “We Are Too Big for This House” and stuck it near the beginning to explain why the speaker is so resentful and still so tender. I used the myth of Narcissus to say things I couldn’t entirely own. At a point I decided I was done. And I accepted it.

What’s next: I’m writing new poems; working on lyric essays; trying to organize readings for poets in Los Angeles when I can alongside Joseph Rios; creating my courses without fear of being fired for the first time; learning to walk away, to eat healthier, to prioritize my heart as much as my body and mind; and growing food and parenting plants.

Age: 33.

Residence: Leimert Park, Los Angeles. But I’m from Fresno, California.

Job: I teach creative writing at UC Riverside and moonlight as a bartender.

Time spent writing the book: The oldest poems in the book are eight years old but are wildly different. The only thing holding them is the memory or the first draft and the essential question I had and that I can still sense in their revised forms.

Time spent finding a home for it: About three or four years. In 2014 I was a finalist for the Andres Montoya Prize, and that’s when I started taking my poetry more seriously. Since then I reworked it until I was offered a contract by Noemi in 2017—the year the real writing began.

Recommendations for debut poetry collections from this year: Why I Am Like Tequila (Willow Books) by Lupe Méndez, Careen (Noemi Press) by Grace Shuyi Liew, Bicycle in a Ransacked City: An Elegy (Alice James Books) by Andrés Cerpa. All fire. All so honest. Read The Full Article Here