by Maia Gil’Adí

From: American Horror Stories Site

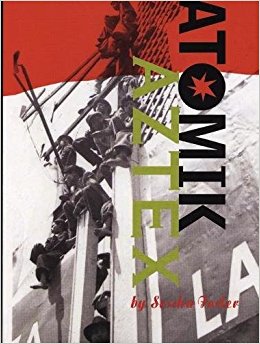

I assigned Sesshu Foster’s Atomik Aztex (2005) as an incentive to begin work on the fourth chapter on my dissertation. In all honesty, I was using my students and our in-class discussions as a sounding board for my own ideas about this complicated novel. Unlike other readings this semester (besides Beloved, perhaps), Atomik Aztex is particularly difficult. It is formally and thematically challenging, implementing postmodern stylistics in conjunction with surrealism, Gonzo “journalism,” and the satirical, which can be baffling for readers. Foster’s mixing of the “low-brow” and “high-art,” popular and consumer culture, Anglo-American and indigenous cultures also present a challenge for readers. My own interest in this book emerges from Foster’s “performance” of Chicanx in this novel and the possibilities that emerge from reading intra-ethnically and across racial and national boundaries.

I assigned Sesshu Foster’s Atomik Aztex (2005) as an incentive to begin work on the fourth chapter on my dissertation. In all honesty, I was using my students and our in-class discussions as a sounding board for my own ideas about this complicated novel. Unlike other readings this semester (besides Beloved, perhaps), Atomik Aztex is particularly difficult. It is formally and thematically challenging, implementing postmodern stylistics in conjunction with surrealism, Gonzo “journalism,” and the satirical, which can be baffling for readers. Foster’s mixing of the “low-brow” and “high-art,” popular and consumer culture, Anglo-American and indigenous cultures also present a challenge for readers. My own interest in this book emerges from Foster’s “performance” of Chicanx in this novel and the possibilities that emerge from reading intra-ethnically and across racial and national boundaries.

As a “native” (I hate using this word) East L.A. writer, Foster is long familiar with Mexican-American and Chicanx culture, especially as it relates to this city. Our class began its discussion of Foster’s novel in the same way as with The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, by examining the novel’s epigraphs. I started our investigation of Atomik Aztexin this way to showcase the importance of framing devices in literature and, in this instance, to underline the literary networks and influences that enhance Foster’s novel. The “prologue” reads as follows:

This is a work of fiction. Readers looking for accurate information on Nahua and Mexica peoples or the Farmer John meat packing plant in the City of Vernon need to read nonfiction. (See Michael Coe and Miguel Leon-Portilla.) Persons attempting to find a plot in this book should read Huck Finn. Also, in this book a number of dialects are used, including the extreme form of the South-Western pocho dialect, caló, ordinary inner-city slang and modified varieties of speech from the Vietnam era. This is no accident.

As some of the English majors in my class observed, Foster’s prologue/epigraph is very similar to Mark Twain’s “Notice” and “Explanatory” note in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, to which Foster’s note alludes:

NOTICE

Persons attempting to find a motive in this narrative will be prosecuted; persons attempting to find a moral in it will be banished; persons attempting to find a plot in it will be shot.

BY ORDER OF THE AUTHOR, Per G.G., Chief of Ordnance.

EXPLANATORY

In this book a number of dialects are used, to wit: the Missouri negro dialect; the extremest form of the backwoods Southwestern dialect; the ordinary “Pike Country” dialect; and four modified varieties of this last. The shadings have not been done in a haphazard fashion, or by guesswork; but painstakingly, and with the trustworthy guidance and support of personal familiarity with these several forms of speech.

I make this explanation for the reason that without it many readers would suppose that all these characters were trying to talk alike and not succeeding.

THE AUTHOR.

As with our discussion of Oscar Wao, this note—funny, irreverent, and challenging—places “high art” (Twain) references alongside the “low” (histories and languages unknown to English-speaking Anglo readers). The combination of these elements (like Díaz’s combination of Derek Walcott and The Fantastic Four) create a world that challenges our understanding of hierarchical knowledge, the literary canon, and even questions of what we consider the “American” nation and “American” identity. These epigraphs initiate students in a discussion of history, and I ask them to consider whether the text presents a counter-narrative, a counter-history, to the historical archive about the U.S.-Mexico border and the conquest of indigenous populations in the Americas. Read Rest of Article Here